Books can come to us too late or too early. Books that come to us too late publish realizations we have already verified and disclose practices we have already incorporated into our lives. For instance, sometimes friends recommend books that go to great lengths to describe man as being asleep and the world as being mechanical. There are many such books—they exist in every culture—but they hold little interest for me because I verify every day that I forget to remember myself and see every day that the so-called rulers of the world act from unconscious desires. I have no use for such books and seldom can read more than a few pages without having a compelling desire to toss the book across the room to say to the writer: ‘Okay, but what’s next?’

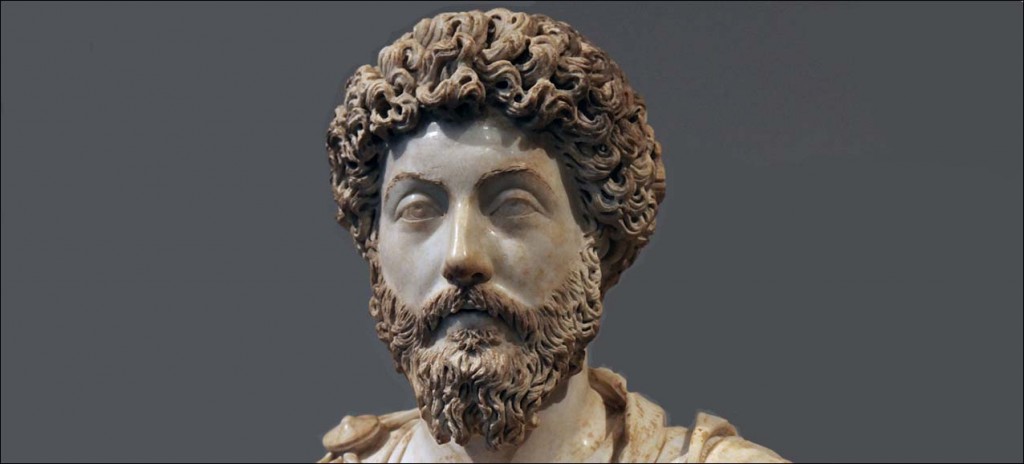

On the other hand books that come to us too early can sometimes fascinate us. The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius was such a book for me. I read it and reread when I was young, twenty-one or twenty two. I guess it’s not surprising that this book was puzzling and wonderful to me. Marcus Aurelius wrote it at the end of his life, at a time when he was an emperor and the commander of an enormous army, and I was a young man with no pretensions to wealth or power. But there was something about his voice, about the way he spoke from the page that captivated me. He didn’t care about I thought or whether I understood him. He wrote for himself, as the title indicates. (The original Greek title means To Myself.) And on top of that there was a quiet confidence that took me a while to comprehend. Eventually what I understood was that Marcus Aurelius was a man who knew himself. Despite illness and grave doubts about the future of the empire, he was comfortable enough in his skin to forget about himself and try to understand the people and the world around him.

In a way it was lucky that I happened on the Meditations at an early age, because it led me to the other stoics, and I was ready for them, particularly Epictetus.

The stoic school was founded by the Greek Zeno of Citium who taught in Athens around 300 B.C., but it didn’t—in my opinion—find a complete written expression until Arrian of Nicomedia, a historian, public servant, military commander, and philosopher wrote out the verbal teachings of Epictetus, a Roman slave. The stoics were particularly focused on the idea of contentment, a concept that I was examining. I was, at the time, recovering from some traumas and disappointments that had left me angry and disenchanted.

Epictetus believed that the mind should be free of passion, and that suffering is the result of trying to control what cannot be controlled.

Work, therefore to be able to say to every harsh appearance, ‘You are but an appearance, and not absolutely the thing you appear to be.’ And then examine it by those rules which you have, and first, and chiefly, by this: whether it concerns the things which are in our own control, or those which are not; and, if it concerns anything not in our control, be prepared to say that it is nothing to you. ~ Epictetus

As it happens the things that are not in our power to control turn out to be transient things—health, property, and life, and unreliable things like possessions and the opinion of others.

Epictetus suggested that the mistake that people ordinarily make is to focus their attention and energy on things that are not in their power to change. He believed that we should focus only on what is in our power to control. For him the idea of what we can control and what we cannot control is the essential key to the understanding of contentment. The idea that we can control transient things like property, wealth, health, and the opinion of others is a very basic illusion that needs to be rooted out. To desire transient things is an inevitable source of suffering, and so the way to contentment is to stop desiring what you cannot have. In the stoic philosophy not all desires are bad. The desire to change the way you think, for example, is a good desire because your thoughts are under your control, or at least can be under your control. But the desire to make another person like or respect you only makes you a slave to a passion that creates a feeling weakness and unhappiness.

In stoicism happiness can be achieved, but first you must learn to distinguish the truth of what is in your power and what is not. As long as you believe, for instance, that you have the power to possess things, you will be subject to feelings of loss and unhappiness when your property is taken from you or damaged. According to Epictetus the correct relationship to all property is that it is on loan. If you are fond of a water jug, you must always remember its nature; that is, that it is made of hardened clay and can be broken. And in the same way if you have a son, you must always remember that he is human and that humans are subject to sickness and death. The main focus of the stoic philosophy is peace of mind. Suffering is viewed as a disturbance of the mind. The remedy to this disturbance is a philosophy that teaches you how to focus your energy on what you can change and how to remain dispassionate about everything else. The contentment the stoic feels is the result of his knowledge that he did all that was possible, and that the rest he managed to accept.

I think the idea that is hardest to understand here is that dispassion or detachment is a necessary component of happiness. We generally think of detachment as indifference to the concerns of others, or as remoteness, and of happiness as a kind of excitement. But what the stoics tell us is that if you want to have happiness that is sustainable, you need to begin to think of it not as great joy or as enthusiastic energy, but as something more like peace of mind. You need to separate yourself from every pleasure that is not in your power to control; you need to be dispassionate because as soon as you give yourself over to the pleasures of transient things, you set yourself up to suffer when these things are denied or taken from you.

The stoic doesn’t separate himself from all pleasure; he simply learns to not identify with pleasures he cannot control because he knows that they are transient and will soon pass away. He contents himself by concentrating on the pleasures and compensations that are under his control and deliberately gives up the rest. The philosophy of the stoic is this: to root out illusion and to change the focus of your energy to what you can control.

I came to know and appreciate more deeply the Stoics ( up to the point I could, and did, call myself “a Stoic”), through M.de Montaigne I had been reading.

And, as he himself says, it is one and only thing, one and only truth in the two formulas: “Know Thyself” and “Work your business”; one part implies the other.

And so it is: “to Know which your business is” and “to Work it out as Being Thyself”.

Great post, to which I wanted to add – or rather correct – one small thing. The main focus of Stoicism isn’t actually peace of mind: it’s virtue, which Stoics see as living in accordance with nature (meaning, in the end, our highest nature as rational beings). Do that, the Stoics say, and you’ll get equanimity, but it’s only a side-effect, not the goal.

Michael, thanks for the comment. Of course you’re right. You express primary aim of stoicism very well: living in accordance with our highest nature as rational beings.

In this article I was more concerned with explaining how we can get to a place where we can live in accordance with our highest nature. And this simple formula from Epictetus, ‘Is this in my power or not,’ seems to me to be the key. As for the emphasis on happiness, it was what I was interested in at the time I read the stoics.

There were other considerations as well. For instance today when we say ‘living according to nature,’ it means something completely different than it did to Marcus Aurelius. “Rational’ has also fallen out favor as a positive spiritual quality. Today is more likely to imply a limitation.

Thanks again for the clarification.