Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception, published in 1954, is still regarded as, if not the best, then certainly as one of the best treatises on the psychedelic experience. Huxley gets so much right about the nature of this type of experience; at the same time he seriously underestimates the potential of reaching these same states through the exercises of conscious evolution. He does seem to have understood the possibility of deliberately creating a higher state of consciousness through the use of substance-free methods. The way he thought about it was as methods that circumvent the reducing valve.

Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception, published in 1954, is still regarded as, if not the best, then certainly as one of the best treatises on the psychedelic experience. Huxley gets so much right about the nature of this type of experience; at the same time he seriously underestimates the potential of reaching these same states through the exercises of conscious evolution. He does seem to have understood the possibility of deliberately creating a higher state of consciousness through the use of substance-free methods. The way he thought about it was as methods that circumvent the reducing valve.

In others temporary bypasses may be acquired either spontaneously, or as the result of deliberate “spiritual exercises,” or through hypnosis. [Huxley’s quotations not mine.]’

There are a few references in the book that refer to the possibility of using exercises like self-remembering and self-observation to ‘circumvent the reducing valve,’ but they are all incidental. The first (above) is at the beginning of the book. Here is another at the end of the book.

When men and women fail to transcend themselves by means of worship, good works and spiritual exercises, they are apt to resort to religion’s chemical surrogates.

Huxley and Ouspensky. We know that Huxley had some exposure to Gurdjieff’s ideas through Ouspensky. Huxley is listed on the dust jacket of The Fourth Way as one of the ‘influential English men’ who attended Ouspensky’s lectures. It is difficult to tell how much Gudjieff’s system influenced Huxley’s ideas because Huxley himself is quiet on the subject, but it is clear from a number of sources that Huxley never considered himself a student of Ouspensky. Robert de Ropp describes a meeting between Madame Ouspensky and Huxley in his book Warrior’s Way, in which Madame Ouspensky shows Huxley around Lyne Place, the farm that the Ouspenskys had set up for their students to engage in physical work. Afterward Huxley quipped that Madame’s teachings ‘consisted of a mixture of nirvana and strawberry jam.’

De Ropp’s estimation of Huxley was that he was ‘too fond on his own opinions to work under the direction of someone else.’

In his last novel Island (1962) Huxley concentrated on the idea of individual spiritual evolution and how a small society could become an ideal state, but how much of it was influenced by Ouspensky and how much of it came from other esoteric sources we will probably never know. It’s also important to note that Huxley’s Island utopia is ultimately undone by greed.

Huxley’s Thesis. It’s hard for us to understand how little the western world knew about the effects of drugs like mescaline in 1954. It’s also important to understand that at the time its use was not illegal. Pockets of psychiatrists and chemists (and eventually the American military) were making experiments in attempts to understand how drugs like mescaline and LSD could fit into the pharmacology of the times. Huxley was a part of one of these experiments and was observed and questioned throughout his time under the influence of the drug. What he brought to the literature on the subject was a connection between the effects of the drug and the whole history (western and eastern) of the mystical experience. Though this connection was not entirely new, Huxley brought it into focus in a way that was hard to ignore.

His basic idea was that mescaline cleansed the perception of the user.

That which, in the language of religion, is called “this world” is the universe of reduced awareness, expressed, and, as it were, petrified by language. The various “other worlds,” with which human beings erratically make contact are so many elements in the totality of the awareness belonging to Mind at Large. Most people, most of the time, know only what comes through the reducing valve and is consecrated as genuinely real by the local language. Certain persons, however, seem to be born with a kind of by-pass that circumvents the reducing valve.

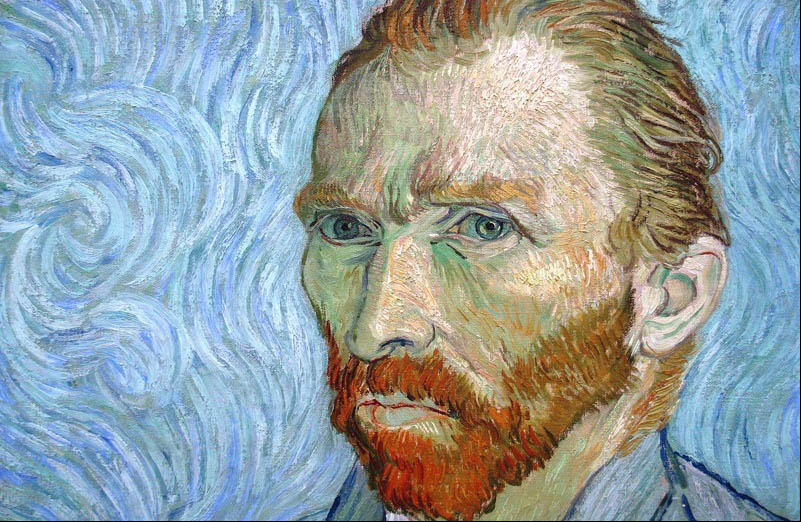

The title of the book is taken from Blake’s ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’. If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is: infinite.

I am told that Huxley’s data on how mescaline affects the brain is no longer thought to be entirely correct. In other words there are new, more up-to-date theories. I will not go into the science of the way the drug affects the body or the brain, but will instead focus on the psychological effects. What is significant here is that Huxley understood that the experience of mescaline was not limited to the users of mescaline.

Each one of us may be capable of manufacturing a chemical, minute doses of which are known to cause profound changes in consciousness.

From what we know about Huxley’s tenuous association with Ouspensky’s group, it seems unlikely that he would have advanced far enough to have studied Gurdjieff’s table of hydrogens, though it is possible that Huxley read about this model in In Search of the Miraculous, which was published five years before The Doors of Perception. It is in this model where it is explained in great detail not only how man’s consciousness is radically changed by introducing two psychological shocks, but also what those shocks are and how we can employ them.

It is important to understand that for many—and this is certainly true for Huxley—mescaline provides some actual experiences of higher centers. The main way the drug does this is by stopping the mind from associating. While under the influence of the drug, when you look at a tree, you don’t associate that tree with the trees that you have seen in the past or with any idea you might have of a tree. You just see it.

I was not looking now at an unusual flower arrangement. I was seeing what Adam had seen on the morning of his creation—the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence.

The Doors of Perception is filled with observations like this.

The associative mechanism is so automatic in our day-to-day life that when it is abruptly removed, we are startled by what we see and feel. Mescaline doesn’t open up higher centers directly, but it forces them to the forefront of our consciousness to deal with and make sense of a world without associations.

If we look at Gurdjieff’s description of the first conscious shock in the table of hydrogens, we can begin to understand why the breakdown of the mind’s associative process can push the user toward a higher perception. (In Gurdjieff’s terms what is happening is that the drug helps bridge an interval in the octave of the inner alchemy of perception.)

An ‘artificial shock’ at this point means a certain kind of effort made at the moment of receiving an impression. It has been explained before that in ordinary conditions of life we do not remember ourselves; we do not remember, that is, we do not feel ourselves, are not aware of ourselves at the moment of a perception, of an emotion, of a thought or of an action. If a man understands this and tries to remember himself, every impression he receives while remembering himself will, so to speak, be doubled. In an ordinary psychic state I simply look at a street. But if I remember myself, I do not simply look at the street; I feel that I am looking, as though saying to myself: ‘I am looking.’ Instead of one impression of the street there are two impressions, one of the street and another of myself looking at it. This second impression, produced by the fact of my remembering myself, is the ‘additional shock.’ ~ In Search of the Miraculous

So what is happening to Huxley under the influence of mescaline is that the shock of seeing without associations is forcing an awareness of himself in the moment. Associations normally allow us to escape to the past, in memories, or to the future, in expectation of what is to come. If we look at a sunset, we might be reminded of the time and what we still need to do before the end of the day, or be reminded of other sunsets that have affected us in the past and reminisce about the pleasures of our youth. These associations replace the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence.

It is also important to understand that not all people who take mescaline will have the kind of experience that Huxley found. Certain personality types, for instance, neurotic or obsessive people, can find that their personalities, when faced with the inability to associate, are disturbed and confused enough to double down on the weaknesses that, to use Huxley’s terms, keep the reducing valve working. Also people with no inkling of the experience of higher centers can find the use of mescaline or LSD very confusing and frightening. I have seen a number of examples of both of these types of people because they ended up, after taking these drugs, in the psychiatric clinic where I worked.

The Dharma Body. In The Doors of Perception Huxley uses the Buddhist term Dharma Body to describe some of his realizations about self and non-self. He is reminded of a passage from a D. T. Suzuki essay where a novice in a Zen Monastery asks ‘what is the Dharma Body?’ and is told by his master that it is ‘the hedge at the bottom of the garden.’

It had been, when I read it, only a vaguely pregnant piece of nonsense. Now it was all as clear as day, as evident as Euclid. Of course the Dharma-Body of the Buddha was the hedge at the bottom of the garden. At the same time, and no less obviously, it was these flowers, it was anything that I—or rather the blessed Not-I, released for a moment from my throttling embrace—cared to look at.

I will not comment on whether or not Huxley’s use of the concept of Dharma Body is correct in the Buddhist or Zen sense, I am not an expert here, but his understanding of self in relation to the perception he is describing needs some revision.

It seems to me that the selflessness that is observed by Huxley is a loss of personality. His personality is lost when it becomes impossible for him to associate the present with past thoughts and actions. It easy to imagine that his education, powerful intellectual capacities, and his family status, which seem to be at the core of his sense of self, were interrupted in a way that allowed him to connect with higher worlds that were already a part of his self, except that they were overshadowed by his personality. His essence, which stands between personality and higher centers, is described very well in passages where he talks about the differences between what he expected and his actual experiences.

From what I had read of the mescaline experience I was convinced in advance that the drug would admit me, at least for a few hours, into the kind of inner world described by Blake and AE. But what I had expected did not happen. I had expected to lie with my eyes shut, looking at visions of many-colored geometries, of animated architectures, rich with gems and fabulously lovely, of landscapes with heroic figures, of symbolic dramas trembling perpetually on the verge of the ultimate revelation. But I had not reckoned, it was evident, with the idiosyncrasies of my mental make-up, the facts of my temperament, training and habits.

What he had not understood was that his essence was very different than Blake’s or AE’s. Some people, like Blake, have a highly emotional essence and people with this type of essence think symbolically, so when they come to communicate their experiences they do so with images and symbols. Art and teachings are communicated through essence, and the array of types of art and teachings give an indication of the wide varieties of essences.

Huxley also seems to believe that some people, like Blake, are born with a capacity for direct seeing.

What the rest of us see only under the influence of mescaline, the artist is congenitally equipped to see all the time.

Though not entirely wrong, the instances of this happening are rare and generally tragic. Later he writes:

The schizophrenic is like a man permanently under the influence of mescaline, and therefore unable to shut off the experience of a reality which he is not holy enough to live with, which he cannot explain away because it is the most stubborn of primary facts, and which, because it never permits him to look at the world with merely human eyes, scares him into interpreting its unremitting strangeness, its burning intensity of significance.

This is a romantic view of schizophrenia. In my experience it is not the burning intensity of significance that destroys the schizophrenic. I doubt an excess of significance greatly harmed anybody, unless, that is, the person is given to concocting dangerous delusions from this significance. The experience of higher centers brings with it a raw energy that is hard to bear, even for students of esotericism who have some preparation. Our bodies are not educated in any methods that allow us to maintain such intensities. What follows for the schizophrenic—really we are only talking about one type of schizophrenia, it is a diverse, catch-all diagnosis—are nervous problems and issues like insomnia, and these, if the mind is weak, lead to more psychological problems like paranoia or megalomania. This is why in the work of conscious evolution a long preparation is usually required. A being that can withstand the intensity of higher energies must be built up over time. Exercises like self-remembering and being present help to focus the strength and endurance of our being, and exercises like non-identification and creating right attitudes help us avoid the pitfalls of delusion and self-importance. Though it is only a partial definition; we can think of being as an ability to transform the rigors of higher energies.

Here we come to one of the most propelling arguments against the regular use of drugs like mescaline: it gives perception but it doesn’t create will, which is an integral part of consciousness. Though Huxley doesn’t offer any real solutions, he does recognize the problem.

It [mescaline] gives access to contemplation—but to a contemplation that is incompatible with action and even with the will to action, the very thought of action. In the intervals between his revelations the mescaline taker is apt to feel that, though in one way everything is supremely as it should be, in another there is something wrong. His problem is essentially the same as that which confronts the quietist, the arhat and, on another level, the landscape painter and the painter of human still lives. Mescaline can never solve that problem; it can only pose it, apocalyptically, for those to whom it had never before presented itself. The full and final solution can be found only by those who are prepared to implement the right kind of Weltanschauung (this can be translated as ‘world view,’ but it really means something more philosophic) by means of the right kind of behavior and the right kind of constant and unstrained alertness.

The Missing Elements in the Mescaline Experience: Will and Unity. Though it is incompatible with the mescaline experience, action is not incompatible with the working higher centers. Mescaline takes us to the gates of paradise, but then eight hours later deposits us in street in front of our house, no closer to paradise than we were the day before. It gives a higher perception, but it cannot give the being that is necessary to create that perception, and it cannot give the unity of being to call up those perceptions at will.

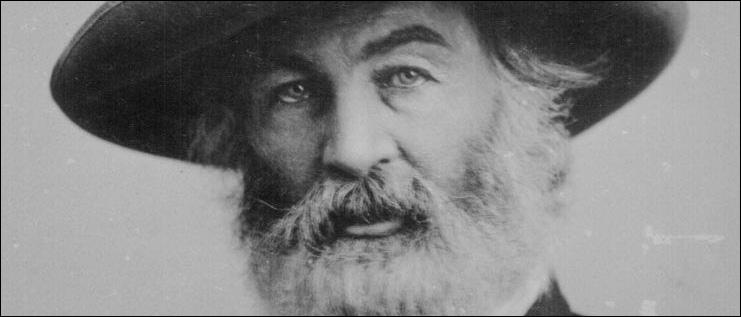

There are stories in the literature of the use of psychedelics that describe how the user attempts to write down the realizations that are important while under the influence of the drug, and then, after the experience, are left with words that are bewildering or mean nothing. There is a particularly good account in A New Model of the Universe in the chapter called Experimental Mysticism.

Once, I remember, in a particularly vividly-expressed new state, that is, when I understood very clearly all I wished to understand, I decided to find some formula, some key, which I should be able, so to speak, to throw across to myself for the next day. I decided to sum up shortly all I understood at that moment and write down, if possible in one sentence, what it was necessary to do in order to bring myself into the same state immediately, by one turn of thought without any preliminary preparation, since this appeared possible to me all the time. I found this formula and wrote it down with a pencil on a piece of paper.

On the following day I read the sentence, ‘Think in other categories.’ These were the words, but what was their meaning? Where was everything I had associated with these words when I wrote them?

Ouspensky doesn’t tell his readers about the methods he used to reach the states he tries to describe, but it is clear to anybody with similar experiences that he used some kind of mind-altering drug. Colin Wilson in his book on Ouspensky suggests that it was nitrous oxide, based on a number of references to William James, who speaks of the use of nitrous oxide in the Varieties of Religious Experience.

In the same chapter there is another more comic passage where under the influence of the drug Ouspensky contemplates the richness of the connections of everything surrounding an ashtray.

I remember writing a few words on a piece of paper in order to retain something of these thoughts on the following day. And next day I read: “A man can go mad from one ash-tray” The meaning of all that I felt was that in one ash-tray it was possible to know all. By invisible threads the ash-tray was connected with everything in the world, not only with the present, but with all the past and with all the future. To know an ashtray meant to know all.

Higher centers are vast worlds that are available to us, but only when we have the courage and focus to call them forward.

There is a passage in Doors of Perception where Huxley writes: One ought to be able to see these trousers as infinitely important and human beings as still more infinitely important. One ought—but in practice it seemed to be impossible.

I realized that I was deliberately avoiding the eyes of those who were with me in the room, deliberately refraining from being too much aware of them. One was my wife, the other a man I respected and greatly liked; but both belonged to the world from which, for the moment, mescaline had delivered me “a world of selves, of time, of moral judgments and utilitarian considerations, the world (and it was this aspect of human life which I wished, above all else, to forget) of self-assertion, of cocksureness, of overvalued words and idolatrously worshiped notions.

He justifies it, but his lack of interest in interpersonal relationships while under the influence of mescaline says more about him than it does about mescaline. He could have used the perception he had gained under the influence of the drug to gain insight into the people around him in the same way he had gained insight into paintings and music and in the folds of trousers. This is to say that when we find ourselves in higher centers, we are tasked with making choices about what we give our attention to, that is, on what subject we wish to deepen our understanding.

There is a passage in In Search of the Miraculous that demonstrates the importance of having a good judgment of the events around us and our own needs in moments of higher centers. This is part of the chapter where Ouspensky describes the remarkable experiences he underwent in Finland, in this case, not under the influences of any drug.

I felt a kind of extraordinary clarity of thought and I decided to try to concentrate on certain problems which had seemed to me to be particularly difficult. The thought came to my mind that in this unusual state I might perhaps find answers to questions which I could not find in the ordinary way.

I began to think about the first triad of the ray of creation, about the three forces which made one force. What could they mean? Can we define them? Can we realize their meaning? Something began to formulate itself in my head but just as I tried to translate this into words everything disappeared.- Will, consciousness… and what was the third? I asked myself. It seemed to me that if I could name the third I would at once understand everything else.

“Leave it,” said G. aloud.

I turned my eyes towards him and he looked at me.

“That is a very long way away yet,” he said. “You cannot find the answer now. Better think of yourself, of your work.”

The people sitting with us looked at us in perplexity. G. had answered my thoughts.

A capacity for direct seeing is a powerful tool both in art and in personal development, but it must be earned either in this life or in a previous life, and when we find our way there, we must be smart and know how to utilize our time in the best way possible in order to help ourselves and others.

Gurdjieff gives us an analogy. He says that man lives in a house with four rooms, but that he spends all his time in one room, the poorest and the most cramped room. And it only by reaching the fourth room that a man becomes the master of the house and knows the immortality of which all religions speak. Gurdjieff explains that the traditional ways—the way of the fakir, the monk, the yogi, and the fourth way—all have the aim to reach the fourth room.

At the end of his description he adds this:

It must be noted further that in addition to these proper and legitimate ways, there are also artificial ways which give temporary results only, and wrong ways which may even give permanent results, only wrong results. On these ways a man also seeks the key to the fourth room and sometimes finds it. It also happens that the door to the fourth room is opened artificially with a skeleton key. And in both these cases the room may prove to be empty.

The room is empty because there is no being to inhabit it.

There are real dangers in the use of drugs like mescaline. When you tinker with the chemistry of the body, or, in this case, the brain, unpredictable results can happen. During my time working at the psychiatric clinic, I met a patient who told me that he had done LSD once and had in his own words ‘never come down.’ Of course I don’t know what kind of dose he had taken or if he was lying to me. LSD was illegal and much of what patients told us ended up in their charts. Still, at the time I could see that he was living, at least for the time, in a perpetual unassociated world, and that this had led to many problems and delusions.

By that time I had already done my own experiments. In my case the results were rather tame. I understood right away that the state induced by the drugs was not limited to people who took drugs. Still I believe that those experiences were legitimate excursions into higher centers. Perhaps they helped clarify certain aspects of higher states and what I could expect later, but even at that age—I was nineteen or twenty—I was already seeking a path to what I now can call conscious evolution. And just so I am clear: all my most significant mystical experiences, before and after this period of experimentation, were not induced by the use of drugs.

I enjoy your lyrics. I agree with your conclusion, which agrees with the position of Mr. G.

I watched an interview with Huxley in 1958, when he said, among other things, “We live in a time of the pharmaceutical revolution.” Today, this revolution is at its zenith. I am afraid that today there are technical-technological possibilities to, on the contrary, close the door between the lower and higher worlds – en masse, without our knowledge and approval, with the help of chemicals, which act on the interface between the two worlds. That would mean an even deeper dream. The brain is just an interface with the basic intellect and working memory.

I like that you are discovering and linking Mr. G.’s esotericism to other sources. Gnosis is not in one place. Gnosis is a mosaic. I hope I have collected a few pebbles.