About a month ago I received a comment from a reader who suggested that my life was nothing but sitting in armchairs and forming worthless opinions, and furthermore, that I would be lucky to change my sedentary life for digging ditches, and that for good measure, I should feel especially fortunate if I get ‘whacked in the head’ in the process.

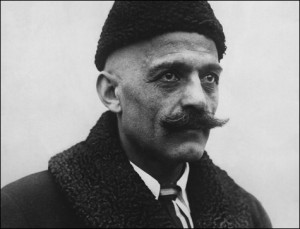

I don’t know this person, have never met him, and he has not commented before, but I suspect that he had read no more than half an article before he formed his opinion of me. He seemed to particularly want to me understand that I was not a teacher and that anyone who trades in ideas is not worthy of using the name of Gurdjieff.

In writing these essays, I have been conflicted over the question of how much to talk about myself and my life. On one side, I have friends who are convinced that to say anything personal will taint the ideas that I want to express with subjectivity, but I also have friends who tell me that there is nothing as sterile and uninteresting as an essay devoid of personal experience. I tend toward the latter view, at least for my purposes, because I want to communicate understanding, not knowledge, and I am convinced that understanding is always personal; that is, it is always an expression of an individual, or rather the expression of consciousness through an individual. Knowledge can exist in a vacuum, understanding cannot; it needs experience to flesh it out.

Part of my hesitation in speaking about myself is that I like the idea of having a private life, but the reality is that I have made so little impact with my writing that what I reveal or don’t reveal will matter little to my day to day privacy. So I have determined to say a little about myself, but after that I want to say something about a few popular misunderstandings about awakening (both in and out of the Gurdjieff movement) that allow justifications for these kinds of criticisms.

First of all I am not a scholar, at least not in any systematic way. I dropped out of a very good university (Miami University in Ohio) after only one year out of a combination of willfulness and a lack of money. I thought I could learn more, or at least more of what I wanted to learn, on my own. The knowledge I possess to this day was gained in a very haphazard way, mainly through reading and other people, and I am certain that there are many gaps and shortcomings in my knowledge of basic subjects.

Montaigne says A learned man is not learned in all matters, but a capable man is capable in all matters, even in ignorance. I have not had the luxury of being learned, so I have aimed to be capable in everything I attempt, whether it is business, writing, or the creation of a soul.

I come from a large family, and in my childhood there was never enough money to go around so that I (and my brothers and sisters) were told that we would be expected to fend for ourselves as soon as we were able. I had my first job at sixteen. I worked part-time in a Walgreens store on weekends and a few weekdays after school. It was a city store, and I regularly sold cheap wine to winos, most of who seem to have been homeless. It was not a difficult job, but it didn’t really interest me, so I moved on pretty quickly. Here is a partial list of the jobs I had held in my life: a sign painter, a laborer on a riverboat, a gas station attendant, a painter of school rooms, a construction worker, a shingler, a factory worker, a caretaker for a man who owned a carnival, a psychiatric technician in a mental hospital, a cook, a restaurant manager, and a technical writer.

As for getting ‘whacked in the head,’ I can assure my critic that I have already had this experience, twice. It took me seven years to recover from the first concussion, and about three months to recover from the second, which wasn’t as severe as the first. Added to this my body is haunted by two serious automobile accidents and a devastating accident that permanently injured both my hands. A Tibetan doctor who has treated me for the last ten years told me recently that if I hadn’t been born with a strong constitution I would certainly be dead by now.

In short I have worked hard much of my life and have had more than a fair share of injury and pain to transform, and my life has been more occupied with experience and change and travel than with the acquisition and dissemination of knowledge. I am sure teaching is an honorable profession (I have two sisters who are retired teachers), but it is an occupation that has never attracted me.

In antiquity there was a letter-writing style called paraenesis. A number of Paul’s letters to his congregations can be said to be written in this style. Paraenesis, as a style, was not used to teach new material, but rather to exhort its readers or listeners—letters at this time were meant to be read aloud—to return to or to continue to live in a good or virtuous way. Another way I have heard it described is that it was the writer’s task to remind his listeners of the understanding they had forgotten. This seems to me to be a very good description of what an esoteric teacher is: someone who reminds his students of their highest understanding, which they regularly forget.

A teacher of esoterism also has to have a certain disposition. The best are patient and are comfortable with repetition, and that is just not me. Without having the credentials of an artist, I have the disposition of one; by that I mean that when I feel the need to communicate a realization or a feeling, I want to find a succinct way to say what I want to say and move on.

Books

For the last three years I have had my own business as a seller of used books. I started this business for two reasons. The first that at this point in my life I am essentially un-hirable—my lack of higher education, lack of any meaningful consistent occupation, and my age—make me unsuitable for almost any kind of decently paid employment. The second is that I have a strong aversion to being under the thumb of a company or an employer. These days employers call themselves ‘job creators,’ act like Zeus when potential employees call, and expect the world from their employees. At my age, I didn’t see why I should commit the bulk of my time and energy to the pleasure of another if I could avoid it.

In Rilke’s poetic novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge there is a passage where the narrator (one imagines this voice to be Rilke himself as he transcribed a number of his letters directly into the book) where he muses on the life of a Paris bookseller:

They are there, sitting and reading without a care; they have no thought for the morrow, have a dog that sits before them, all good-natured, or a cat that makes the silence still greater by gliding along the rows of books, as if it were rubbing the titles off their spines.

Perhaps this was a legitimate image of a bookseller of a hundred years ago, but it is has nothing to do with the modern-day book business. First of all, the vast majority of books are not sold in shops but online and mailed directly to the customer. Even iconic bookshops like Moe’s in Berkeley and Powell’s in Portland sell online now. It is also a crowded field, as there are many small online sellers that are trying to either make a living or to supplement their income with the buying and selling of books.

The first hurdle is the acquisition of a stock of books. We call this aspect sourcing and it is the most competitive part of the business. The sources are wherever you can find books cheap enough to resell. In general that means finding books, as a lot, that can be sold for a minimum of five times what you pay for them. The most common sources are library sales, estate sales, secondhand stores, and the buying of libraries (usually from the relatives of a recently deceased bibliophile).

Library sales can be profitable, but you have to know what you’re doing and be quick. At a good library sale say in Palo Alto, or somewhere in the east bay like Albany will attract as many as 200 people, and lines begin to form an hour or more before the sale begins. Of course the majority of the buyers are not resellers, but maybe 10% or 15% are, so at a good sale you may be competing with 10 to 30 sellers. There are also many smaller library sales, where you may only be competing with a few other resellers. Most libraries in California have sales. The way it works is that the libraries ask the people in their communities to donate books, and instead of putting the books on their shelves, they hold sales, and take the money from these sales and pay their employees or their electric bill. Before COVID 19 this was the norm, and most libraries formed FOL (Friends of the Library) societies, which organized the sales. These societies are almost always made up of volunteer workers and members who pay a small donation, usually fifteen or twenty dollars a year, and for that fee are allowed to buy books at ‘preview’ sales. I am a member of maybe ten of these societies all around Northern California. At this time COVID 19 has closed many of these sales, though some have reopened in a very restricted way.

Fortunately during the pandemic it is still possible to buy libraries from individuals, which is the best option because generally you are only meeting with one person and protocols, like wearing masks and social distancing, can be agreed upon beforehand. I find, compared to other sourcing methods, that I get the best overall value by buying libraries. The downside is that you generally have to take everything, and so it becomes your responsibility to deal with the books that are damaged or have no value to resell. The fees for booksellers on Amazon and eBay are high, so it makes no sense to sell books under a certain price. (The lowest I will list a book for is seven dollars plus shipping.) To give you some idea of the numbers I can process, in the last five weeks I found and purchased six full or partial libraries, adding up to something like 1700 books, but maybe 500 of those books were unsalable for one reason or another.

I could write quite a bit more about this profession, but it is probably enough to say that it requires a good memory, a knack for sizing up others, patience, a capacity to bargain and make quick decisions, and a strong back. Anybody who has ever moved a library of 30 boxes of books in the middle of summer, one time from where they were stored and then a second time to a shop at the other side, can easily imagine that this profession has not a lot to do with sitting about in armchairs. In 2019 I traveled over 10,000 miles to source books, sometimes over 500 miles in a two-day period.

Who We Admire

Any man can speak truly; but to speak with order, wisely, and competently, of that few men are capable. ~ Montaigne

There is something ridiculous about the pedant, a learned man who lacks the discipline to use his knowledge in a way that benefits his soul. This is not in question. The question that now faces us is whether the remedy to this problem is to glorify the ignorant who move from action to action without consideration, without knowledge, and without any understanding of the consequences of their decisions.

If we look at the way our society measures a man, it is plain that we respect fame and wealth above other qualities, even when fame has nothing to do with a reputation of goodness or understanding and when wealth is inherited or acquired by taking advantage of others.

A man who measures a man by fame lacks his own judgment; he defers to others for his respect. His calculation must be that if so many other people like and respect a man, then he must have something worthy of admiration. He doesn’t examine the man by his own set of values, but sees that others value him and follows suit. We see this in the world of literature all the time. How many people know that Shakespeare is a great writer by their own judgment? How many people know firsthand that his poetry is unmatched, that he essentially created the complex, internally motivated character, or that his plays are masterpieces of stagecraft? If you ask most people why they think that Shakespeare is a great writer, assuming they answer honestly, they will tell you that they know because they have been told that he is great. And if hadn’t been for a small group of Shakespeare’s friends, who pulled together the texts and published the first folio, we might know next to nothing of this great mind.

In our age, as in other ages, a good reputation and notoriety are almost equally admired. Beauty (and handsomeness for men) and talent may be important factors, but merit is not often part of the equation. And nothing shows our disregard for merit and character more than our admiration of the wealthy for the sake of their wealth. Does a man who owns seven houses and a dozen cars have better judgment than a man who owns one car and one house? Perhaps he is a better judge of how to turn a thousand dollars into ten-thousand dollars and ten-thousand dollars into a million dollars, but does that make him a good man, or even a good judge of character or events, or does it not rather show that he is a shrewd calculator of the weakness and ignorance of others and of the value of the goods he trades in. When I pay five hundred dollars for a group of books that I know are worth twenty or thirty thousand dollars, and could have easily paid more and still make a profit, does that make me worthy of the respect of others?

Cicero thought that merchants should be considered vulgar because their profession required that they lie a great deal. Montaigne was more forgiving and believed that no profit is made except at the expense of others. In other words that it is the way of nature, and that we should not lose sleep over it.

The merchant does good business only by the extravagance of youth; the plowman by the high cost of grain; the architect by the ruin of houses, officers of justice by men’s lawsuits and quarrels; the very honor and function of ministers of religion is derived from our death and vices. ~ Montaigne

The reality is that we admire the people who have what we want or have what we imagine that we want. We admire powerful and charismatic men because we want to control other people; we admire the wealthy because we imagine that their life of luxury will bring us pleasures we do not now have, we admire the young because their lives are not as limited as our own, and we admire beautiful people because we see that they are more eagerly admired.

And is it not even more ridiculous to admire a man because his father or grandfather made a lot of money? Do we also wish that we had different parents? Democracy was supposed to free us from the myth of admiration solely on the basis of ancestry. Instead, we have replaced our admiration for the well-born with an equally unfounded admiration for men born into wealth.

It is a rare man who admires another for his patience or for his capacity to suffer greatly without complaint, or a man, to use Shakespeare’s words:

Whose blood and judgment are so well commingled,

That they are not a pipe for Fortune’s finger

To sound what stops she please.

~ Hamlet

We dare not admire men of being who have changed themselves through effort and the transformation of suffering because that would mean that we would desire to bring on ourselves the necessity for the same effort and the same discipline and endurance; instead, we prefer to imagine that fortune is going to hand us luxury, power, and pleasure. You cannot scan any list of new movies and TV shows these days without finding a dozen or so whose main characters have developed miraculous powers, not by any effort of theirs, but by some accident or hereditary impossibility. The producers of these stories know what they are doing; they know that they will be more successful in pandering to the imagination of the public, than in showing the realities of change of being.

Judgment

Judgment is a tool to use on all subjects, and comes in everywhere. ~ Montaigne

In our language a man may be said to have good or sound or clear judgment, or he may be said to have a poor or bad judgment; he may even be said to have no judgment at all. When I worked in the psychiatric hospital, the head nurse who hired me defined madness—our patients—in a very broad way. She said that insanity was the inability to live in or negotiate the outside world. Besides the rather broad sociological implications of this statement, it struck me that what she was saying was that our patients lacked a sound or clear judgment. Judgment is what allows us to negotiate the world without injuring or insulting or confusing the people around us, and most of our patients had not managed to accomplish this. Our deluded patients confused their family and friends with visions of an alien world, one that they alone inhabited. Our depressed patients insulted or hurt their loved ones with snapshots of a world that was so terrible or overwhelming that it was not worth living in. And our criminal patients hurt others because they had no control over their greed or addiction or passion. The problem with this definition is that in a world like the one where we now live, where men of power and influence suffer from serious and disturbing delusions themselves, it is harder for ordinary people to find models of good judgment. If they see successful people who prosper by bad judgment, why should they not imitate those people, after all, they have found success?

Let’s examine this a little. If a man makes a considerable amount of money by polluting a river, why should he be said to have poor judgment? He has used his faculties to get what he wanted, and is that not an example of good judgment? What is missing here is that there is always a wider picture and that there are consequences to our judgments. A man of poor judgment doesn’t see the consequences of his actions. A criminal who is caught defrauding and cheating people who didn’t foresee that he would end up in prison cannot be said to have good judgment for the years before he was exposed and bad judgment after he was caught. His judgment was bad from the beginning. And the people who admired his skill at making money during the years before he was exposed simply didn’t have a judgment that was far-reaching enough to include his inevitable fall. In the same way, the man who pollutes a river in order that he may profit in the short run also has poor judgment. Though he may seem to get away with it—he may even die before the effects of his crimes are felt in a big way—he will suffer the consequences, if not in this life, then in another life or in worlds invisible to us. The difficulty for us, as observers of the crime, is that in order to understand that his judgment has been a poor choice, our judgment must be based on spiritual understanding, and not simply on cause and effect in the physical world.

Part of what having a sound judgment means is an ability to see clearly and not be misled by people who are either deluded themselves or are trying to delude others for their own profit. It can be said, for instance, that if we vote against our own interests or if we trust a politician who has a clear history of lying and being untrustworthy, then we lack clear judgment.

So what are the building blocks of sound judgment? First of all, I would say self-knowledge. If you do not know yourself and what is important to you, you will not have a gauge to judge people and events. After that we must look to the three aspects of consciousness: consciousness (or perception), because without the capacity to observe ourselves looking at the world, our judgments will be based on an imaginary self; will, because without some control over our vices our judgments will be dictated by our weakness; and unity, because without it, our judgments will be sometimes sound and sometimes poor.

Though fortune may beat us down—even in situations when our motivation is pure and our judgment is sound—it is with our judgment that we assert first of all our character and eventually the perception gained by the experience of our souls. It is essential and comes in everywhere because it informs our decisions.

Is Intelligence Really a Problem?

I cannot keep a record of my life by my actions, fortune places them too low, I keep it by my thoughts. ~ Montaigne

The mind like our other faculties can be misused. Just as the strength of the physical body can be used to hurt others and the perception of the emotions can be used to humiliate others, a clever mind can be used to insult and demean others. I have already mentioned the problem of pedantry, but there is another more disturbing misuse of the intellect of which we must say something: sophistry.

In Plato we find that the main rivals of Socrates were the sophists, but what sometimes doesn’t come through in the dialogues is the real threat to Athenian life that Plato saw in this philosophy. A sophist is a professional arguer. He only endeavors to win; whether his arguments are true is not important to him because he doesn’t believe that there is an ultimate reality. In other words a sophist believes that every view is just an opinion, so there is no obstacle to using any argument, however fallacious, as long as it brings success. To a sophist a good argument is not one that is sound in meaning and fact, but one that persuades.

From this definition you can see that the contemporary sophist is alive and well. Today they are prominent in politics, the law, and advertising, and have done especially well with the rise of the internet and social media. They give the intellect a bad name in the same way bullies give physical strength a bad name.

In my youth I regularly attached myself to people that I determined knew or understood concepts or exercises that I wanted to understand. My understanding was so lacking that I did not feel that I had the luxury of choice: old or young, beautiful or plain, rich or poor, rude or polite, it didn’t matter to me; I took their understanding and then figured out how to implant it in myself. But I have to admit that in my old age I have become more satisfied with my understanding. Whether this is natural or healthy I do not know. I am not so fixed that I have not made many corrections to these essays that have been suggested by friends and strangers. I take correction, but I am not as tolerant as I should be of assassinations to my character from people who do not know me, and, most of all, I am not forbearing of people who tell me what I can and cannot understand. I have worked hard and some cases suffered to gain the understanding I have, so I am not interested in arguing with people who want to steal it away from me because they have not verified it and cannot stand that other people understand more than they do, or because they believe I am an intellectual and consider intellectuals to be stupid when it comes to experience, or because they don’t like my face or my politics or that I am no longer young.

I should admit here that I have what is called a pet peeve. It is this: the modern trend in popular spirituality to demonize the mind.

My business requires me not only to search for and buy used books but also to know something about what new books are being published. In the category of ‘New Age’ books, I find that every year there are scores of books published that are about the benefits of being present. Oddly most of the authors who write these books are not truly spiritual, but are using the exercise of being present for worldly, transient aims like wealth, happiness, and personal power. They seemed to have forgotten, or never learned, that being present is an exercise that is fundamental for the pulling together of the materials that make up the soul. That aside, those that do dip their toe in the esoteric use of being present almost universally find one enemy in the practice of the being present: thinking.

They have observed that when they are trying to be present that the train of their effort is inevitably disturbed by what they call thoughts. But really what they are observing is imagination or stray thoughts, not thinking. They find that the key to the practice of being present is a quiet mind. And they are right in their observation. Stopping thoughts is a powerful exercise in any spiritual practice, and should be practiced regularly. And if it is practiced correctly, it will create a fertile ground for understanding, and understanding, at its inception, is never in words, is never intellectual, but if it is to be fixed, the mind needs to play its part.

It is not enough to count experiences, we must weigh and sort them; and we must have digested and distilled them, to extract from them the reasons and conclusions they contain. ~ Montaigne

What is generally missed about thinking is that the active element is not thinking, but observation. Descartes was wrong when he said I think therefore I am. It was a great mistake that empowered an army of pendants and second-rate academics. A better formulation would be: I am when I observe my thoughts, but thoughts could just as well be replaced with movements or emotions or sensations. It is observation or remembrance that creates being. As we know all processes must have three elements or forces to create results. The most effective triad for thinking is where observation the active force, the passive force, or material to be acted on, is the thoughts themselves, and the third force is the motivation, which sets the process in motion, which could be the wish to learn, or the wish to communicate, or the wish to understand.

The appearance of higher centers is a powerful and exhilarating experience. The question we have to ask ourselves is do we want these experiences to become a part of being, to have them affect our life, even when higher centers are absent? In order to do this, we must learn to fix the understanding they bring.

One of the foundations of the fourth way as described by Gurdjieff is the idea of intentional revelation. In other words we don’t have to wait for the understanding of higher centers, but rather can learn to evoke that understanding. Imagine being able to bring the specific understanding you need to transform any situation, any negative emotion, or any suffering in the moment as it is happening. That is what we are aiming for. But if we are to accomplish this, we must infuse our being with the understanding as it comes to us, and to do that, we need to begin to observe and organize our thoughts.

Admiration of great men is often a double-edged sword, and this is certainly the case with Gurdjieff. Too many people who admire Gurdjieff admire either his vices or else attach themselves to teaching methods that Gurdjieff alone could pull off. In order to teach like Gurdjieff, you need not only to have his level of being, but also certain predispositions in essence, as, for instance, his type and center of gravity. Lacking these, your teaching will be at best an imitation and at worse a corruption of the spirit of Gurdjieff’s ideas. In either case it is false or delusive.

A trend that is now popular for people who know a little of Gurdjieff is to take on his manner of insulting his students. They want to be powerful, as Gurdjieff was, and to use that power to control others or to prop up their vanity. But it was not his manner that made Gurdjieff powerful; it was his being, his ability to exist when everyone around him could not. And these people are often hard on intellectuals because they have read in books that Gurdjieff was hard on Orage and Bennett and Ouspensky. But the reality is probably different; the evidence seems to suggest that Gurdjieff was, at times, hard on all his students, and we just happen to have more accounts of his interactions with intellectuals because they were the ones who were compelled to write accounts of his teaching.

It should be remembered that Gurdjieff called his group The Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, and that it is the very definition of the fourth way that we work on all our lower functions at the same time. It is a way of balance and is contrasted to the three traditional ways which require intensive work in one center and to a large extent exclude the other two. We are all imbalanced, but the fourth way should make us more balanced, not more intolerant and more limited.

The more a man understands, the greater will the results of his efforts. This is a fundamental principle of the fourth way. ~ Gurdjieff

Balance is always a more difficult path than extremity because balance generally needs transformation and effort and understanding to come into being. Extreme ideas and actions are driven by passions and identifications and these tend to disappear or appear small in the face of higher centers.

If we are going to imitate Gurdjieff, wouldn’t it be better to imitate his enormous compassion, which is on display in accounts by Fritz Peters, Thomas de Hartmann, and Katherine Mansfield, to name a few, or imitate his detailed, systematic style of teaching that we find depicted in In Search of the Miraculous?

We need to be occasionally reminded that the Gurdjieff/Ouspensky system of enlightenment is not an accredited teaching. You cannot take a course for two or four years and then set yourself up as a teacher. And nobody who understands that nature of esoterism cares about your linage or the fact that your teacher was taught by a student of Bennett and that Bennett was taught directly by Gurdjieff, or how clever you are at insulting people and getting them to do your bidding. If you want to gain our respect show us first that you can control yourself, and then tell us what you understand and what is important to you.

I stopped caring what people say about me a long time ago, and say now, as the Roman philosopher Epictetus said of his critics: if they knew me better, they would say worse. I have my vices, as do all men. What I want now is to figure out a way to fix the understandings that I have worked so hard to realize. Every man, as he faces old age and death, must hope to take his understanding, and only his understanding, into the next world. It is that disembodied understanding that I defend when I ask: is intelligence really a handicap to spiritual work?

Any quality can be a handicap if we identify with it, health can be a handicap to spiritual work if we identify with it, but nobody is suggesting that we should neglect our health in order to do the work. A dancer may become an expert of the movements, but if he thinks of himself as a dancer rather than as an observer of his self, then this too is a denying force to the work. In the same way, if an intellectual thinks of himself as an intellectual, rather than an observer of himself, it is also a hindrance. Despite these possibilities, it does not help anybody to demonize the lower functions. We should instead lay the blame where the fault lies, with the identification.

Stupidity, as Montaigne says plainly, is a bad quality, and to glorify it is worse: it is dangerous. It is remarkable that this needs to be said, but in our age, when every day we see examples of willful ignorance in the news, it bears repeating often. If we want to be people of spirit, then we need to take a little responsibility for the world in which we find ourselves. We do not know on what level we work, and if we see popular trends in the world at large that promote delusion and ignorance, then we, at the very least, must not bring those trends into our teaching.

Balance is not sexy, and it is seldom newsworthy, but it will get us to where we want to go. We are not three-brained beings by accident. The instinctive/moving function, the emotional function, and the intellectual function each provide us with a key to the understanding of higher consciousness. The emotional center may be the closest to higher centers in energy, but the intellectual center is closest in disposition.

Study and contemplation draw our soul out of us to some extent and keep it busy outside the body, which is a sort of apprenticeship and semblance of death. ~ Montaigne

It just happens that we live in a world where a large portion of the population would rather listen to a man speak nonsense with charisma and emotion, than listen to a level-headed man speak the truth.

If we were perfect, spiritual beings we would not need to form judgments; the world and other people would not be separate from us; we would see the world as it is and people as they are because our soul would have the ability to encompass the being of the people around us and the entirety of the circumstances that affect us. Another way of saying this is that our judgment would be perfect and instantaneous. But since we are far from perfect, we need to employ the faculties we have been given to negotiate the world and form judgments, and one of those faculties is the mind.

If we were perfect, spiritual beings we would not need to form judgments; the world and other people would not be separate from us; we would see the world as it is and people as they are because our soul would have the ability to encompass the being of the people around us and the entirety of the circumstances that affect us. Another way of saying this is that our judgment would be perfect and instantaneous. But since we are far from perfect, we need to employ the faculties we have been given to negotiate the world and form judgments, and one of those faculties is the mind.

Thank you for this. If I hold up the snapshot you have shared of yourself with us, I see a comforting self resemblance.

If a conscious being was meant to have a degree of pride, such as Gurdjieff, I believe he would be proud to say that he knows you and that you are a child, a son of his.

I think therefore I am.

The 1st I is perhaps Instinct,

Think ( the mind )

I am ( the emotions. ? )

A man number 7 might simply say.

“I” the rest is superfluous.

I appreciate your thoughtful article. Thank you and many blessings

There is the basic and ‘pocket sized’ idea in the Fourth Way of work with our “attitudes”, it is mental dispositions. These ought to be intentionally developed on the basis of our verifications, and this works to channel our further experiences toward those same verifications, “feeding them” let’s say, and preparing the ground for further verifications and understanding.

It’s a simple principle.