A[/drocap]t the psychiatric clinic where I worked, I was asked one morning to go to our front offices to admit a new patient. This involved helping the patient fill out about a dozen forms. The patient I interviewed that morning had been brought in by her sister and her brother-in-law, and she—let’s call her Mary—refused to answer my questions, and so her sister had to answer for her.

In the interview it came out that Mary had been tricked into coming to the clinic—she had been told that they were going to go shopping—and so she was understandably mad at her sister for essentially deciding that she was crazy and having her admitted to a psychiatric hospital. About halfway through the admission the sister tried to coax Mary into speaking to me. She said, “Go on, Mary, tell the man what you told me this morning at breakfast.”

But Mary wasn’t interested in telling me anything. She sat rigidly in her chair with her lips pressed firmly together and her hands folded in her lap.

After a fairly long pause the sister said, “She told me that God had made her pregnant.”

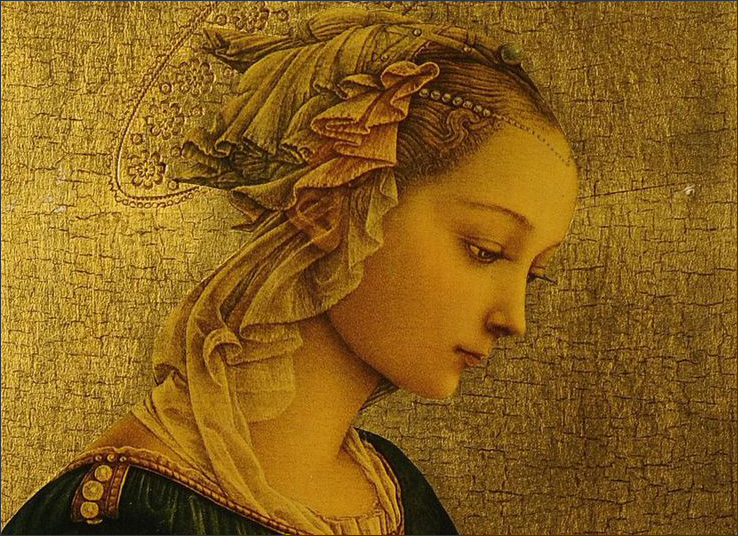

Mary looked as if she were about to be martyred. She wore a black dress and a white scarf, which made her look vaguely like a nun. Her clothes were neat and clean, and she had fine brown hair, thin features, and light, transparent skin. Her sister, by contrast, was more ruddy and healthy-looking, with a mass of black, curly hair.

I took a special interest in Mary’s case. I was intrigued. How had this woman convinced herself that it was her fate to give birth to the next messiah? My idea was to ask Mary about the moment of her divine conception. I wanted her to describe to me, in the plainest terms, where she was, what she saw, and how she felt. But I knew that it wasn’t going to be easy to get her to open up. As far as Mary was concerned, she was the persecuted martyr, and we (the staff at the clinic) were the spiteful and unrelenting Romans.

I had to wait a week, but I did eventually draw her into a conversation. This was in the afternoon when most of the other patients had gone to downstairs to activities. I found her alone in the ward kitchen. She was standing at a counter carefully pouring the contents of a can of Pepsi into a clear plastic cup. I asked casually, “Why didn’t you go down to activities?”

“I have to go to the hospital later and have a test.”

“Which test?”

“The one the doctor wants me to take.”

“But which test is it?”

She looked perplexed, as if she wanted to speak, but something was holding her back. I helped her along: “Did the doctor tell you what the test was for?”

“He said they can tell if a woman is with child.”

“A pregnancy test.” Of course I already knew about the test. This was the way our psychiatrist had decided to settle the question. I said, “What will you do if it’s negative?”

She looked at me as if she didn’t understand.

I said, “Negative means that you’re not pregnant. Positive means you are.”

“I know it will be positive.”

“When did you first know?”

“Before I came here.”

“But where were you exactly?”

“At home.”

“In the kitchen?”

“No. In my room.”

“At your sister’s house?”

“Yes.”

“Do you remember the moment it happened?”

“Oh yes,” she said. “I couldn’t forget that.”

“Was it in the morning?”

“No. In the evening.”

“What were you thinking about?”

“I wasn’t thinking at all. I had just finished watching a movie on television. I have a little set in my room. The movie was about the Civil War. I stood up after it was over, and that’s when it happened. I remember standing watching myself and seeing everything in the room: the television, the bed, the dresser, the mirror, and the window where the light was coming in. It was all the same, but it was different.”

“How was it different?”

“It was all… smaller. The television was on, but it didn’t mean anything. Only the outside was real.”

“What was outside?”

“The yard,” she said, as if she had suddenly lost interest. She drank some Pepsi from her cup.

“The yard was real?”

“And the trees and the sky, but not the room.”

“Why not the room?”

“Because in the room everything had been invented by a man. I wouldn’t have noticed it by myself. The angel helped me. I saw it the way he saw it.”

“How?”

“From above.”

“Did you actually see the angel?”

“No. I felt him.”

“What was it like?”

“It was like, like nothing I’ve ever felt before, like knowing that everything was right.”

“But when did you know about the child?”

“I realized it later.”

“When everything was normal again?”

“Yes. When I thought about it, I knew it couldn’t be anything else. What else could it mean?”

I didn’t need to ask anything more. I understood. Pictures flashed before my mind: pictures of Mary standing at the window of her room with the television playing behind her; of her sister sitting at breakfast listening in amazement to Mary’s revelation; and of our psychiatrist in his office systematically dissecting Mary’s sexual frustration. I wondered if it could be that simple. Could it be that Mary’s original experience was legitimate and that her delusions came later, when she tried to interpret what had happened? But how else could she have explained it? She had to fall back on her Christian mythology; it was all she had. When I pressed her to describe, and not to interpret, it came up perfectly sane. Well, almost.

Passages that describe the possibility of a different awareness, of a state where a person is more awake and sees what is normally hidden, can be found scattered throughout philosophy and literature, and even in the New Testament. But what did Mary know of philosophy and literature? She knew the New Testament and probably little else. And she certainly didn’t think of the Gospels as mythology or literature. If she thought about it at all, she probably regarded them, not only as the truth, but as historical fact. Clearly she had experienced something in her room that was both important and meaningful to her, but given her education, what other interpretation could she be expected to come up with? She explained her experience in the only way she knew how.

Incredible as it sounds, I think Mary found herself, after watching a movie on television, in a state of consciousness that has been, for at least as long as men have cared to record their perceptions, the aim of every mystic and saint. Only in Mary’s case the experience surpassed her. Whatever benefits she gained from her experience were certainly outweighed by the negative consequences of being locked up in a psychiatric hospital and given drugs she had no power to refuse.

2

I wanted to tell this story because I think it illustrates the uneasy relationship between esotericism and myth-making. We’ll get back to Mary, but first I want to define esotericism and mythology.

Esotericism is an explanation of the laws, principles, and methods that govern enlightenment and describe the worlds it uncovers. It tells us not only what we must do to awaken higher centers, but also how we can view ourselves and the world around us from the point of view of higher centers.

Mythology is essentially is the communication of cultural truths through the art of story-telling, but for the purposes of this essay I will limit myself to myth-making as it used to communicate (or hide) esoteric truths.

The first and most obvious question is why do esoteric truths need to be told as myths, stories, and parables? Why not just explain the principles of esotericism in clear, everyday language?

The answer to this is complex because the aims of the myth-makers throughout history have been very diverse. In some societies it was necessary to hide esoteric knowledge because it was seen as opposed to the religious traditions of the times. Clearly the first Free Masons felt this, and really the medieval Catholic Church was not very tolerant of any organization that it saw as competitive, especially when those organizations proposed interpretations of texts that differed from church doctrine.

And it is well known that Jesus concealed parts of his teaching in parables..

I talk to them in parables, because they have sight but do not see, and hearing but do not hear or understand. ~ Matthew: 13.13 (Richmond Lattimore translation)

You might think from this passage, and from others like it, that Jesus believed that there would be some people who heard his parables that could understand their inner meaning, but, in fact, he had to interpret his parables for his own disciples. He says to them:

I tell you that many prophets and good men have longed to see what you see, and hear what you hear. ~ Matthew: 13.18

Clearly Christ divided men into two circles: the inner circle that was privy to ‘secret’ interpretations, and the outer circle that was not.

The ancient Kabbalists were even more cautious. Originally only men with a rigorous preparation were allowed to read the texts from the Kabbala. This was because they believed that these texts were, in the hands of the unprepared, a road not only to misunderstanding but also to madness. Sometimes this is interpreted as meaning that the knowledge contained in the Kabbala was so complex that an unprepared man, in an attempt to understand these perplexing books, would be driven insane. But maybe the Kabbalists were pointing to another possibility. I don’t believe that knowledge itself can cause madness—really the mind is very good at buffering, or blocking out, ideas that it doesn’t understand—but I do believe that the sudden appearance of higher centers can cause madness. I have seen it many times. In people who are unprepared for it, the appearance of higher centers, even for a few minutes, can be a very disorienting and disturbing experience. Higher centers give us information about ourselves, about other people, and about the world that contradicts some very basic tenets of any normal functioning society. It is one thing to read as an analogy that men are asleep or that they are machines, but it’s something else entirely to see it. In my time at the clinic I met a number of patients who were convinced that everybody was asleep, and one woman who decided that her friends and family were machines. Like Mary, these experiences surpassed them.

If we were connected with higher centers in our present state, we would go mad. ~ P. D. Ouspensky

In my two years at the clinic I met maybe two dozen patients who described what I recognized as perceptions that could only be encountered through the working of higher centers, but none of those patients were prepared to deal with what they felt and saw. They reacted with paranoia or depression or manic behavior. Part of the problem was that in order to benefit from higher centers, you first have to value the insight higher centers give. And as far as I could see, none of these patients, certainly not Mary, had any wish to attach themselves to a perception that contradicted what was considered acceptable by their friends and family. Instead of wanting to find ways to reconnect with higher centers, they attempted to explain it away.

Preparation for higher centers requires valuation because if you have no valuation for what higher centers bring, then you will certainly not be willing to make efforts to create higher states. In other words you will not be willing to study and to experiment with exercises like self-remembering and the transformation of negative emotions.

3

We have two very different approaches to the presentation of esoteric knowledge in the examples of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky. Ouspensky in The Fourth Way lays out the system in plain and very clear language. He made no attempt to hide or disguise any of the knowledge he acquired as a pupil of Gurdjieff. On the other hand, when it came time for Gurdjieff to write a description of the system he taught, he wrote Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson. Beelzebub’s Tales hides the knowledge that Gurdjieff wanted to communicate in the ruminations of an extraterrestrial known as Beelzebub. The tales, which recount the many follies and triumphs of the ‘three-brained beings’ (men) of the planet Earth, are told to his grandson Hassein as the two of them travel home on a spaceship. And on top of this, Gurdjieff, in order to require of the reader a certain amount of effort, invents words for basic concepts and writes in a style that is anything but easy to understand.

If you want to read Gurdjieff’s book, you are required to dig around and think and interpret. But listen to what he writes later, after he started to hold readings in order to observe the effect Beelzebub had on the people that heard it.

I, for the first time very definitely… understood the following: The form of the exposition of my thoughts in these writings could be understood exclusively by those readers who, in one way or another, were already acquainted with the peculiar form of my mentation. Every other reader… would understand nearly nothing. ~ G. I. Gurdjieff (Life is Real Only Then When ‘I Am’)

Basically what Gurdjieff is saying is that the only people who will understand Beelzebub are the people who already know the system that Beelzebub teaches. And I don’t think this is only true of Beelzebub; it is true of the majority of esoteric works that are couched in myth, storytelling, and symbol. Remember Christ had to interpret his parables for his own disciples.

The point I want to make is that myth-making is, at best, an unreliable vehicle for the transmission of the principles and methods of conscious evolution. The ideas are not intuitive; they need to be explained except in rare exceptions.

This is not to say that storytelling and symbolic writing are not without value; they have enormous value, and there are many good reasons to embed esoteric truths in mythology. Really myth and symbol are the language of higher centers. A well-told myth or symbolic story can create an emotional state in the same way music or a beautiful painting can. In other words it can bypass the intellectual center and talk directly to higher centers, but the ideas need to be explained if we are going to be able to create a consistent level of effort. You need to know where you’re going, but you also need to how to get there. Conscious evolution is the how of esotericism. It is not all of esotericism. Fourth-way methods and principles are not terribly complex; they can be understood by the majority of people who make an effort to understand them. The problem isn’t their complexity; the problem is these ideas are very good at pointing out the delusions of the people who begin to try to put those ideas into practice. This is Gurdjieff’s stated aim for Beelzebub:

To destroy, mercilessly, without any compromise whatsoever, in the mentation and feelings of the reader, the beliefs and views, by centuries rooted in him, about everything existing in the world. ~ G. I. Gurdjieff

When writers or teachers want to make esotericism popular, they inevitably eliminate unpopular truths and the necessity of effort. It always amazes me the lengths people will go, and the things they will say, in order to avoid the simple truth that awakening requires inner effort for a definite, usually long, period of time. It also has to be understood that these kinds of ideas require precise definitions and vocabulary, and that language changes very quickly, sometimes within a couple of generations

The ideas of this system can never be popular so long as they are not distorted, because people will not agree that they are asleep, that they are machines. ~ P. D. Ouspensky

A story that is misunderstood may very well be passed on because of the illusion people create around it. Whereas a system of knowledge that teaches uncomfortable truths is more likely to be dismissed and persecuted.

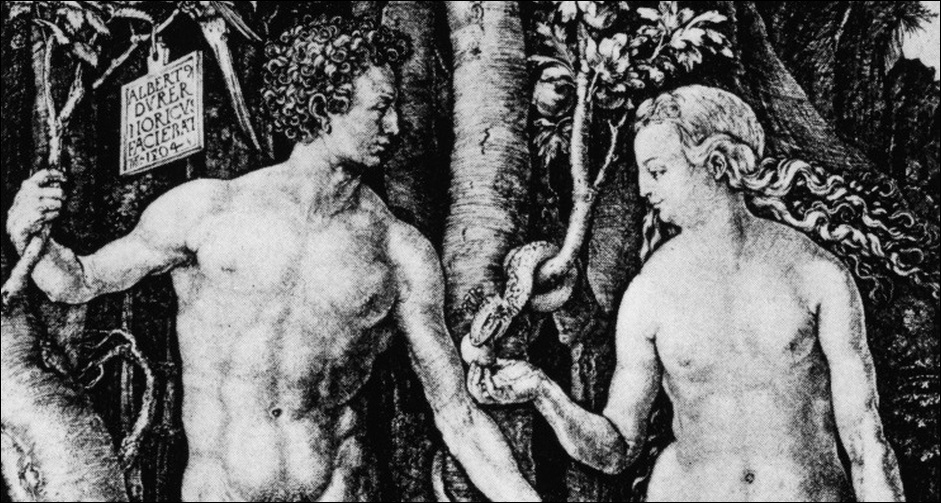

I was raised Catholic and had the New Testament read to me so often as a child that many of the stories became part of my memory. But it was only as a young man, when I began to study esotericism, that I started to understand the New Testament texts. As a teenager I, like Mary, took the story of the virgin birth literally, only I didn’t believe it. I assumed that the writers of the gospels were naive or ignorant. But now I know that this story was not meant to be taken literally. I know that virgin mother represents a certain quality of emotion (Ouspensky called it the intellectual part of the emotional center) that we all possess, and that this part serves, supports, and ultimately brings forth higher centers. You see, if the gospel writers had described this process in the language of the times, it probably would have become distorted very quickly and then, just as quickly, have been forgotten, but because it was told as a fantastic story, it was retold again and again, written down, and remembered.

I was raised Catholic and had the New Testament read to me so often as a child that many of the stories became part of my memory. But it was only as a young man, when I began to study esotericism, that I started to understand the New Testament texts. As a teenager I, like Mary, took the story of the virgin birth literally, only I didn’t believe it. I assumed that the writers of the gospels were naive or ignorant. But now I know that this story was not meant to be taken literally. I know that virgin mother represents a certain quality of emotion (Ouspensky called it the intellectual part of the emotional center) that we all possess, and that this part serves, supports, and ultimately brings forth higher centers. You see, if the gospel writers had described this process in the language of the times, it probably would have become distorted very quickly and then, just as quickly, have been forgotten, but because it was told as a fantastic story, it was retold again and again, written down, and remembered.

A very nicely crafted essay containing not only questions and loosely referenced conjectures, there are “brain-storms” that contain elements of great spiritual content, but also may contain delusions and demented aspects. A VERY delicate study.

One note…. All the medicines for depression like SSRIs were originally developed to treat epilepsy. And Childhood temporal Lobe Epilepsy has been connected to religiosity and hypergraphia, the compelling urge to write ceaselessly. — Yours, Richard Lloyd

I needed to hear this. Very interesting! Did it really happened?

I will take note of the books you mentioned. Our personal quest for higher knowledge and meaning is something that dogma and indoctrination can’t control. It is a very lonely road and one has to make the effort to go a step further and persist beyond the literal.

It is True: like Plato says, men are very pleased in hearing of ‘gods’, of ‘another world’ and so forth, but are vey unwilling to hear about themselves.

Frank, yes, it did happen, pretty much the way I described it. I had a number of people ask about Mary, so I might as tell what I know about her. First of all nothing terrible happened to her. Though she refused to talk, she was really a very sweet woman, and was well liked among the staff and the other patients. The doctor did give her drugs. (Patients who refused to talk were given certain drugs to help them ‘open up.’ ) The pregnancy test was negative of course, but she just refused to believe it. I guess it was about week after the test that she had her period, and that did convince her. I don’t remember her being terribly disappointed about it. She was released from the clinic after six weeks.

Thanks for sharing this. What happened to Mary happened to me too, almost identical in the way those around me handled my opening. The great thing is I found teachings, G.I. Gurdjieff and all of the materials in esoteric teachings helped me, when the world of psych weas a dead end. The bible had been read to me by my grandmother regularly, and it too was a huge part in my mytho memory, but, as you said, taken as history and somehow effected my emotional life. I was doing art and was able to connect through my work, quiet and focused on the world around me, but not yet in me. The birth, I actually had bith pangs and milk flowed from my youths body, never had any thing like it occur on that virgin birth again, but other revelations have come through and I know it is higher center communing. It is so sad that the psychological working community has such harsh methods dealing with spiritual awakenings. Such a hard world, yet, there is no easy way is there. Thanks again for this article I have been waiting for. I wish it would get a lot of reads, and maybe others much earlier than I was able to, find out about the esoteric teachings and can find their way in a brotherhood sooner. I know now that they are with me in heart mind, always. Very helpful, being too many look for it to be there and isn’t in the secular world.

It also says in the bible not to cast pearls before swine, and I think, milk before meat.

As for the virgin Mary’s birth in the bible, truth, is it literal? Saying that it is not, who does that belief belong to?

In order to strengthen the highest in a person (to teach), one must address the highest. That is the inner meaning of the pearl story.