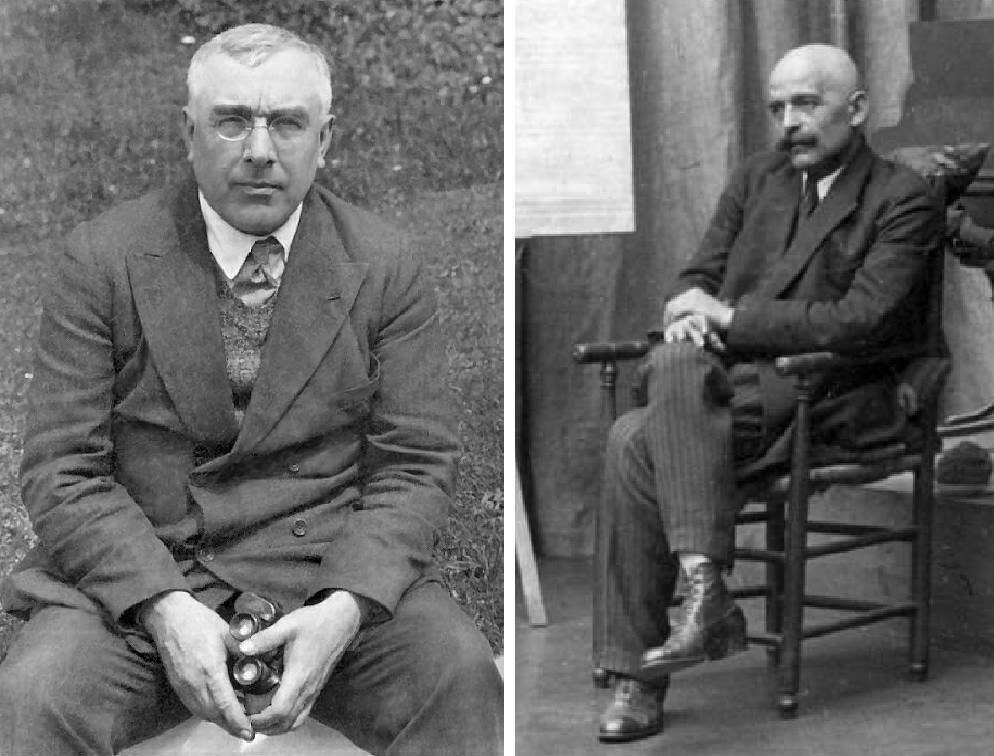

I discovered the writings of P. D. Ouspensky from a book by Colin Wilson called The Occult. Wilson quotes a long passage from The New Model of the Universe, which so struck me that the next time I was in a used book store, I inquired about Ouspensky. The owner of the store didn’t have any of his books, but he knew of Ouspensky and gave me his opinion of the man. ‘He was great writer,’ he said, ‘He wrote a brilliant book called Tertium Organum, but then he became associated with a charlatan named Gurdjieff and went downhill from there.’

I discovered the writings of P. D. Ouspensky from a book by Colin Wilson called The Occult. Wilson quotes a long passage from The New Model of the Universe, which so struck me that the next time I was in a used book store, I inquired about Ouspensky. The owner of the store didn’t have any of his books, but he knew of Ouspensky and gave me his opinion of the man. ‘He was great writer,’ he said, ‘He wrote a brilliant book called Tertium Organum, but then he became associated with a charlatan named Gurdjieff and went downhill from there.’

As far as I know Ouspensky’s reputation outside the Gurdjieff movement has not changed substantially in the last 50 years. He is certainly less fashionable, but he is still considered by many to have been a brilliant philosopher/writer whose first book rivaled Aristotle and Francis Bacon. Tertium Organum means ‘third canon of thought.’ Aristotle wrote Organum, and then Bacon wrote Novum Organum (1620), ‘new canon of thought.’ It was a bold move, some would say arrogant, for the young Ouspensky to associate his first full book with Aristotle and Bacon.

But that is not what I want to talk about here. It is Ouspensky’s reputation inside the Gurdjieff movement that I want to speak about. Many of the articles and comments I have read about Ouspensky in the last two years seem to me to be either unfounded or based on a misunderstanding of what the system is and what it represents for all us. My plan here is to look at some of the most common complaints and respond to them individually. But I before I get into that, I want to point out something that people who criticize Ouspensky tend to forget: besides Gurdjieff, no one in the early days of the movement did more to support, clarify, and promote the work than Ouspensky. Many of Gurdjieff’s most important students came through Ouspensky, and when Gurdjieff needed money to buy the Chateau du Prieuré at Fontainebleau, much of the money that was raised came from Ouspensky’s friends. And as far I know In Search of the Miraculous is the only book about Gurdjieff’s teaching that was authorized for publication by Gurdjieff.

I will cover five complaints that appear to me to be the most common and most repeated.

1

That Ouspensky was just an intellectual and didn’t really learn to practice the work.

This is by far the most common judgment leveled against Ouspensky by his critics. This criticism is largely based on a misconception that the work must manifest through a moving/instinctive activity like dance or that a teacher of the work must, like Gurdjieff, be powerful and charismatic.

Gurdjieff was hard on all his intellectual students, including Ouspensky. He made Orage dig ditches when he came to the Prieuré, and he is reported to have told Bennett, ‘Never once I see you struggle with yourself. All the time you are occupied with your cheap animal.’ But he was their teacher and he more than anybody knew their weaknesses, and how to help them balance their lower centers. A ‘man’ in Gurdjieff’s terms is someone who had created a balance; that is, an ability to use and respond from his instinctive/moving, emotional, and intellectual brains as the situation required. So we must assume that Gurdjieff’s intellectually centered students (men number three) needed to develop their moving and emotional functions, but at the same time we must assume that his instinctive/moving and emotionally centered students (men number one and two) needed to develop their intellectual functions. It is unrealistic that to suppose that a man like Ouspensky could have excelled in the movements; in the same way, it is unrealistic to suppose that Gurdjieff’s best dancers could have developed intellectual abilities rivaling Ouspensky.

In reality there is no perfectly balanced man. It is an ideal. Perhaps Gurdjieff himself came closest to realizing this ideal, but even he had his imbalances. Essence means being strong in some areas and weak in others. It is what makes us different. Some people are born with an agile moving function, and some, like Ouspensky, are born with an agile mind. To some extent we all have to play to our strengths if we want to serve the work, because it often turns out that our weaknesses are also where our greatest strengths lie.

We also need to remember that the fourth way is not a way of dance, or of art, or of any other activity. It is a way of understanding. And if you read The Fourth Way, certainly still the best group of lectures by Ouspensky, what you find is not an intellectual expounding ideas, but rather a man who understands the difficulties and complexities of inner work who tries his best to bring his students around to the necessity of effort. In other words, a man who knows the work from the inside, a man who understands its difficulties because he has experienced those difficulties himself. It is a book that can only be appreciated when we begin to try to make those same efforts.

From all accounts Ouspensky was not charismatic, at least not as charismatic as Gurdjieff, still, he must have had something to have been able to attract so many students. We must careful not to mistake charisma for higher consciousness. (Here I am defining charisma in the ordinary, popular sense, as one who arouses fervent devotion and enthusiasm, not in the theological sense of possessing the power to perform miracles.) There are many politicians and performers in everyday life who possess the power to attract a fervent group of devoted followers who clearly have no grasp or experience of higher centers. Higher centers may manifest in a charismatic essence, as was the case with Gurdjieff, but a charismatic personality is not evidence of higher consciousness, and the lack of a charismatic personality is not evidence that higher consciousness is lacking.

2

That Ouspensky only repeated Gurdjieff’s ideas, that he no original ideas of his own.

This criticism is the result of a misconception of the nature of esoteric knowledge. First of all, they were not Gurdjieff’s ideas. He makes it plain that he acquired his knowledge through a long search. In other words, he was given the ideas, just as Ouspensky was. Gurdjieff was not very forthcoming about his sources, but he never claimed to have invented the ideas of the system.

Esoteric ideas come from higher mind. They are not invented so much as rediscovered. This is something that is difficult for us to comprehend at the beginning. Our democratic ideals have blinded us to the idea that men can have a radically different being; that is, that some men, because they have mastered the exercises of esoterism, have a greater capacity to understand. Essentially all esoteric systems are the same, whether they were practiced by the ancient Egyptians, Medieval Christians monks, 13th century Sufis, or the generations of people of the Gurdjieff movement, who have learned to practice self-remembering and non-identification. Higher mind means the working of higher centers. The idea is that when higher centers work, it is possible to see what is normally passed over in sleep. And the knowledge that comes from this perception, particularly the knowledge of the methods and the exercises that are needed to connect to higher centers, forms the basis of esoteric knowledge.

This from the first paragraph of The Fourth Way:

The most important ideas and principles of the system do not belong to me. This is chiefly what makes them valuable, because if they belonged to me they would be like all other theories invented by ordinary minds—they would give only a subjective view of things. ~ P. D. Ouspensky

Gurdjieff and Ouspensky claimed the knowledge of the system not by inventing it, but by mastering its exercises and disciplines. Now it is our turn to do the same.

3

That Gurdjieff used Ouspensky for his connections but didn’t believe in his inner work

The argument that Ouspensky used Gurdjieff is just as strong. Gurdjieff had the knowledge that Ouspensky had spent most of his adult life trying to uncover, and he spent his years with Gurdjieff trying to put it all together in a working system, and then left him after he had what he wanted. On Gurdjieff’s side, he gained access to circles that he would not have had access to without Ouspensky. Ouspensky was an important intellectual and journalist in Russia. His lectures, before he met Gurdjieff, are said to have attracted one thousand people. Ouspensky also basically doubled Gurdjieff’s number of Russian students by organizing his Petersburg group, and he quickly became Gurdjieff’s go-to person to teach the basics to new students. When Thomas De Hartman joined Gurdjieff’s group he was straightaway sent to Ouspensky to be caught up.

I think it can be said that the relationship between Gurdjieff and Ouspensky was less personal than it is usually made out to be. What I mean by this is that when Ouspensky helped Gurdjieff by finding sources of income or by sending his students from England to the Prieuré, he had a large enough perspective to understand that he was not helping Gurdjieff as much as he was helping the work itself. Gurdjieff was an agent of the work, but so was Ouspenky, and Gurdjieff understood this, and always included Ouspensky in public lists of his students.

At the same time this does not mean that there was not friendship, or even love, between the two men. We know, for instance, from In Search of the Miraculous that Ouspensky was invited to Gurdjieff’s family home and that he met Gurdjieff’s father. Gurdjieff had an enormous love and respect for his father, and I seriously doubt that he would have invited Ouspensky to meet him if he did not consider him a good and trusted friend.

4

That Ouspensky made a mistake when he separated from Gurdjieff.

We cannot know what would have been better for Ouspenky’s personal work: staying with Gurdjieff or leaving him, as he did, and starting his own group in London. Clearly Ouspensky was conflicted by his decision to separate from Gurdjieff. But at the same time, I think we can take his word when he explains at the end of In Search of the Miraculous that he found something destructive in Gurdjieff’s methods. In 1923 Ouspensky ‘went fairly often’ to the Prieuré and was invited by Gurdjieff to live there. He considered it, but this was his final conclusion:

I could not fail to see, as I had seen in Essentuki in 1918, that there were many destructive elements in the organization of the affair itself and that it had to fall to pieces. ~ P. D. Ouspensky

The question here isn’t whether Gurdjieff was destructive. All the evidence is that he was destructive. The question is whether his destructiveness was a teaching method, or whether it was simply a weakness of his character. It is not a simple question, but there is evidence that Gurdjieff considered it a teaching method and that he could control it. Fritz Peters’ book Childhood with Gurdjieff includes several behind-the-scenes accounts that seem to demonstrate that Gurdjieff had a remarkable amount of control over his emotional outbursts. It is also obvious to anybody who understands Rodney Collin’s map of human types that Gurdjieff was a Mars/Jovial type, which means that he had an essence that was given to directness and destruction on the Martial side and to arrogance and harmony on the Jovial side. In other words, his essence clearly dictated not only his character but also his teaching methods.

Gurdjieff, more than Ouspensky, Collin, and other fourth-way teachers, felt that his students wouldn’t appreciate the knowledge unless they paid for it. This belief accounts for some of what Ouspensky called his ‘acting,’ that is, telling off-color jokes and humiliating his students. It also accounts for his writing style, which was deliberately made convoluted and opaque.

It’s easy for us to imagine that, if we had known Gurdjieff, he would have either appreciated our work or that we would have been able to not identify with his onslaughts. But I seriously doubt that he would have spared any of us, or that many of us would have had the being to stick it out as long as Ouspensky did.

The reality for us is that if Ouspensky had stayed with Gurdjieff, the movement would not be as diverse and robust as it is now. Ouspensky, by settling in England, was forced to reform the system in the English language, which turned out to the prominent language of the twentieth century. He was also responsible for setting a standard of terms and ideas for the other English writers who were influential: Nicoll, Bennett, Orage, and Rodney Collin, all of whom he taught.

5

That Ouspensky was an alcoholic, and was consumed by nostalgia for his old life in Russia

I have seen the accusation that Ouspensky was an alcoholic made four or five times in recent comments and articles. By all accounts Ouspensky was a heavy drinker, but then so was Gurdjieff, and nobody is calling him an alcoholic. Many people in the movement seem to feel that Gurdjieff had complete control of his weaknesses and that Ouspensky was completely controlled by his weaknesses. I’m guessing that the reality is that both men had a level of being that allowed them to regularly access higher centers, but at the same time both men had a human side, and that this human side was subject to excesses and weakness.

To some extent our attitude about Ouspensky depends on who we believe. I tend to think that Rodney Collin’s accounts have more validity because he spent more time with Ouspensky than most of his critics. He was also there at the end of Ouspensky’s life and recorded what happened in those remarkable last months. In his letters Collin doesn’t allow himself to be drawn into the dispute of who was right and who was wrong, or who was more conscious and less conscious, but rather sees Gurdjieff and Ouspensky as part of a larger revelation.

I believe that Gurdjieff and Ouspensky were the two chosen agents of at least one stage of a new revelation. They were partners and complements, chosen because they represented and could transmit opposite aspects of the same truth. Two poles have to be separated for electric current to jump between them and make light. ~ Rodney Collin

In a pamphlet that is not very well known called The Herald of Harmony Collin writes that Gurdjieff and Ouspensky represented two forces in a triad, that Ouspensky played the first or positive force and that Gurdjieff played that second or negative force. He also says that it was his role to play the third or invisible force.

You can also say that the three men in their relationship to the outside world represented one of the three aspects of higher centers: Gurdjieff, will; Ouspensky, consciousness; and Collin, unity.

Like Gurdjieff, Collin at the end of his life experimented with language in order to try and find a different way to communicate the experience of higher centers, except that he went in the opposite direction, instead of a convoluted and opaque style, Collin experimented with an abbreviated or poetic style. This is the way he describes Ouspensky in The Herald of Harmony:

Grew old, invisible. Behind the crumbling façade of the body constructed a new edifice, whence HE looked out. ~ Rodney Collin

It is well documented that Ouspensky liked to sit around a table with his closest students and drink and talk and to some extent reminisce. This seems to me to a very Russian activity. When I went to Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union and met with a new generation of Russians interested in the Gurdjieff/Ouspensky work, I found myself many times in exactly the same situation; that is, sitting with three or four people around a kitchen table in a flat in Moscow or Saint Petersburg and drinking vodka and talking about the work and its men and women.

Nostalgia is a strange emotion. Unlike sadness or joy, it is not connected to the moment, but is rather connected to the past. This fact alone makes it suspect. But the key to transforming any emotion, including sadness and joy, is non-identification. It is our identification with emotions that make them mechanical. If we can bring self-remembering (the present) to a moment of nostalgia, what happens is that we create a connection between the present and a moment in the past, and if the emotion is strong enough, it can create an arc through time, connecting not only the moment in the past with the present, but also all the moments in between. And this is close to a definition of higher consciousness, which can be seen as an experience of a longer time, or of a line of time. Ouspensky even seemed to believe that if this longer experience of time was powerful enough, that it could extend into the future.

Through a theoretical study of the question I came to the conclusion that the future can be known, and several times I was even successful in experiments in knowing the exact future. I concluded from this that we ought, and that we have a right, to know the future, and that until we do know it we shall not be able to organize our lives. ~ P. D. Ouspensky

6

I know this comment is going to upset some followers of Gurdjieff, but I have found that in meeting with hundreds of new students of the movement in 8 or 9 countries that the students who knew only Ouspensky’s books were more prepared for inner work than the students who knew only Gurdjieff’s books. Of course, it was best when they know both Gurdjieff’s and Ouspensky’s works. The problem with new students reading only Gurdjieff is that his powerful character overshadows the knowledge and people try to imitate that rather than trying to create a foundation of knowledge and being for themselves. Gurdjieff also attracts a group of people who are no good for the work; that is, people who are not interested in connecting to higher centers but are only interested in learning how to control and manipulate other people. They see Gurdjieff not as a teacher of conscious evolution, but as a ‘black magician’ or at least as a man who knew how to get what he wanted in a worldly sense.

At university, I had a creative writing instructor who often said to us, ‘This line tells us more about the writer than it does about the character.’ And this is the way I feel about many of the criticisms I read about Ouspensky, that the writers tell us more about themselves than they do about Ouspensky.

People who disparage great men to enhance their own image fool only those who share the same prejudices and only hurt their own possibilities.

You have to do gigantic work if you want to become different. How can you ever hope to get anything if you hesitate and argue on the first steps, or don’t even realize the necessity for help, or become suspicious and negative? If you want to work seriously you have to conquer many things in yourself. You cannot carry with yourself your prejudices, your fixed opinions, your personal identifications or animosities. ~ P. D. Ouspensky

You have to do gigantic work if you want to become different. How can you ever hope to get anything if you hesitate and argue on the first steps, or don’t even realize the necessity for help, or become suspicious and negative? If you want to work seriously you have to conquer many things in yourself. You cannot carry with yourself your prejudices, your fixed opinions, your personal identifications or animosities. ~ P. D. Ouspensky

Anybody who has tried to make consistent efforts to bring self-remembering and the non-expression of negative emotions to their day-to-day activities, knows that this work is difficult both to start and to maintain. It is only when we become serious about inner work, and to some extent awaken to our own possibilities and limitations, that we become grateful to have help, wherever we find it.

There is that scene in In Search Of The Miraculous when Ouspensky first meets Gurdjieff. G wants to know if his story, The Struggle Of The Magicians, can be published in a paper. O states it is too long then proceeds to leave, at which point shortly after he says to himself: “I must at once, without delay, arrange to meet him again, and that if I did not do so I might lose all connection with him.” I have often considered that this thought was planted in O’s consciousness remotely by G himself, that G knew this man would bring the work forward in a modern way. So in other words, G actually brought O to himself, through the ether.

The Prieuré was always going to close (even before it opened), and G knew this. But the school acted as one of three lines, as a kind of temporary force, to keep O moving forward in the way that he did. For example, when O looked upon the schools’ recent focus on movement and dance, and upon the lieutenants G had thus selected, he was repelled back to his studies. This in my opinion was deliberate: O would go on to publish the guiding lights while G would help some other students advance as far as they could.

So, Tim, would it be fair to say that your view of Ouspensky is that Ouspensky was almost like an egregore, created by Gurdjieff to expound the Work and bring it to others?

Excellent piece.

Many of those that profess to understand the work will blame ouspenskies teachings rather than their own inabilities.

The beauty of the book “The Fourth Way” is how the writer has been able to catch the subtle differences in how a question is asked, to reflect the level of the student asking that question.

Thanks for this article William.

I found myself too, at times, replying to some criticisms toward Ouspensky; and their “bottom points”, if they can be call’d this way, seem’d me to be: -if the one was right *then* necessarely the other was wrong.

Or : -if Ouspensky was not a concious being, *then* he assuredly has been the worst ever being on earth, such that the devil himself is repell’d at.

And, by sure, it all comes down to your ending, for -what do I really know or can know, of another’s being?

As Gurdjieff said, as we are we do not even know when we scratch our head. And if we begin to see this, which is very true, by far we would not dream to lay such extreme judgements, and on things of such scale and importance.

An excellent article for which I am thankful. Not only for learning new things about those two great men, but because each piece of info reminds me of how important it is to always try to be present and not accept anything as given but always wonder and be grateful for this opportunity to see things in a new way.

My theory on this is that both of them, O and G, had planned this ‘event’ from the outset. As Gurdjieff implied in his work many times a Master cannot teach No1, 2 3 4 men, they simply would not understand him, but he could teach No 5 and 6 men as they are the only ones who could relate to him…

I think G realised how powerful his personal teaching was, and people coming to his work, would either be put off by G’s enormous presence (apparent in his writing and in life), or would heavily identify with G (as said above), rather than his work…But he wanted this ancient teaching to continue..So what if he got No4 or maybe No5 men (Ouspensky,Nicol,Bennett et al) to continue the work, and in the process create a conflict ‘friction’ struggle in the process…

nb. We must remember that Fourth Way is also the way of the cunning ‘sly’ man..And we can see many examples of this in Meetings with…

Yes it is reported that Ouspensky was more challenged in the Instinctive/Moving Centre and Emotional Centre and tended to veer towards the Intellectual side where he felt more comfortable. I think this haunted the psyche of O, and led to his heavy drinking and bohemian life, at this point I think he realised he would never get any further in consciousness and he merely abandoned the work in himself but still continued teaching with a heavy heart…which is tragic.

I disagree with the writer of the article who condones O’s drinking and identification with nostalgia as ‘ very Russian activity’..this I dispute. Nostalgia was clearly O’s chief feature, and because it was heavily crystalised in his Emotional centre he was not able to wrestle with and destroy it, but he couldn’t accept the fact that he had lost all those years and not reached full enlightenment..The fact of the matter is, anyone who can even reach to be a full No4 man let alone No5 or No6, has done an incredible amount of suffering and struggle in his short life and should not be despondent.

I cannot imagine Ouspensky ‘willingly’ saying that G’s work in France was becoming destructive, and he had to leave.

He met G in 1915. G taught him for 10 years, but they knew each other for 32 years..

We also must remember that it was a always master and pupil relationship, never equal friends in the mechanical way. It’s clear in the writings of G that he loved mostly all people he who were attracted to him in a conscious,benevolent way (apart from nuns and priests).

He saw G in action during the war, taking care of his family and entourage (using incredible life skills) in the Caucasian mountains, he knew this was no fake teacher, or no ordinary man, he knew this man was the real deal. But G treated him no different than anyone else, this also annoyed Ouspensky, the fact that he was never given ‘special attention’ and at times he even refused to do a few of the arduous tasks assigned to him..These were usually tasks G was giving him to work on Emotional and Moving Centre. I’m sure at times he hated G, but he was in awe of him and he knew he could never surpass him or even equal him..I think this also added to his dispondency .

Gurdjieff was consciously trying to destroy Ouspenskys ego, but he gave up, so he had other plans for him..Ouspensky thought that because of his high intellect he should be treated differently, but G treated the Tramp and the King with the same reverence or indifference. Ouspensky was simply a snob.

My conclusion..As I said above, they(Gurdjieff mainly) planned this ‘friction’ in the works, as it was probably used as a shock, in an octave concerning the Work…And it was clearly successful as his work is still moving…Although not all of the groups and literature around are genuine, but neither are christian groups or their writings.

To say that Ouspensky leaving and betraying G, and then G being sad and disappointed…No this is award winning acting and ‘cunning man’ tacticts again by G. Gurdjieff was a full man, we don’t know if he was ‘fully enlightened’….but he wasn’t far from it..Events like this would not have bothered this man, he would have changed things around, he had the will to destroy all the groups that sprung up when he was alive, and he did destroy a few of them, so why not Ouspenskys. He knew the limited power and essence of Ouspensky more than Ouspensky knew himself, but he also knew the work had to continue and Ouspensky was the best candidate ..

Gurdjieff was handing his work over to lesser conscious men, but he was handing it over to apply a ‘shock’ to The Work

These are only my opinions sprinkled with reportage from well known documented sources

Nb..I’m fairly sure if Gurdjieff were to read this he would probably laugh uproariously, pat me on the back, take me into the garden, point to a shovel and say ‘Now you dig hole’.

Amazingly high standard of comments. Informed (mostly), witty, rueful at times. This convinces me that The Work lives. Thank you to all contributors.

I am not an intellectual, but Ouspensky”s Tertium Organum and subsequently The Fourth Way ,altered my way of thinking. I did try reading ” All and Everything” guess I`m just not ready for it

Alcoholism is so little understood yet the distinction between a heavy drinker and a true alcoholic is so simple. I myself am a recovered alcoholic, sober now many years and I have been working intensively with other alcoholics for the past eight years. It has been true to my experience that the difference between a heavy drinker and an alcoholic is that, provided the right environment and support a problem heavy drinker can stop or moderate. It will not kill them. How they get the right environment and support is another matter. The real alcoholic cannot drink at all without a progression of certain symptoms. They may be sober for some time but once they take the first drink it creates a physiological response that manifests as a craving for more. Over time this response will grow so powerful that it eventually takes priority over all else.

The second symptom is, once they recognise they cannot drink safely at all they make a firm resolution to stop. They usually do for a period, sometimes years, but they always return to drinking regardless of their prior decision and the known consequences their drinking will bring about. When they do the physiological response kicks in with it’s progressive nature and they’re back in the cycle. They will repeat this ad infinitum. They will throw away an entire life they’ve built up around themselves for the sake of the drink. Sometimes they’ll make excuses, rationalise how and why it will be different this time. Regardless, they always make the same decision. To go back on their prior commitments to remain sober. In this sense, the choice to drink or not is an illusion. They have no choice in the matter. The result is always the same. A heavy “problem” drinker is not faced with this sort of insanity. Given the right treatment and motivation they can stop or moderate.

I am not saying recovery from alcoholism is impossible. It is absolutely possible if one is to find god. I’m not talking about the god from the bible. I’m talking about a spiritual centre, it’s impossible to describe. It can only be experienced. I know people who live these principals in their lives and have this connection yet would never know it themselves. They don’t need to understand or articulate it. It can also be achieved in half measures although the life one gains as a result is only marginally favourable to the one they had as an active alcoholic and long term sobriety is unlikely under these conditions (cases of suicide are high).

It should not be so hard to determine if one is an alcoholic or not. I’m not saying Ouspensky was or wasn’t. I don’t know because I like the author here only just came across the mention of Ouspensky while reading Colin Wilson. I was aware of Ouspensky but had never heard him described as an alcoholic which is what caught my interest. As part of my own recovery I have become obsessed with matters of the spirit/consciousness.

I have dealt much with the medical world in regard to treating what they now term alcohol use disorder. In renaming this disease they have done away with the distinction between an alcoholic and a heavy problem drinker. They’d never been very good at seeing the distinction. Regardless, it is regularly viewed as one in the same when they are distinctly different. They apply the proven scientific methods of treating a heavy problem drinker to both categories and then wonder why they have exceptionally low rates of success.

I apologise if this is way off topic. I am the child of an alcoholic parent, I have a son myself. This disease affects so many and causes so much needless suffering because the scientific and medical communities refuse to look beyond the world of conventional understanding. They ignore the evidence because they do not have a method for measuring or formalising their understanding of it. I hope this may be helpful to someone who reads this