In chapter thirteen of In Search of the Miraculous Ouspensky asks Gurdjieff how he can recreate the emotional state that propelled into the series of extraordinary experiences he had undergone in Finland.

‘Sacrifice is necessary,’ Gurdjieff told him and then added: ‘But if there is anything in the world that people do not understand it is the idea of sacrifice. They think they have to sacrifice something that they have. In actual fact they have to sacrifice only what they imagine they have and which in reality they do not have. They must sacrifice their fantasies. But this is difficult for them, very difficult. It is much easier to sacrifice real things.’

When I was a young man, I was a bit obsessed with this passage. It seemed to me that Ouspensky had concisely formulated what I needed in my work. He had some remarkable experiences and wanted to be able to ‘evoke’ them at will because he understood that, if he could do this, he would be able to find the rest.’I also had had some remarkable experiences and was trying to find a way to repeat them, and was certain that if I could figure out how to do this that I too would be able to find the rest.

I was intrigued by Gurdjieff’s answer, but clearly I was one of the people who didn’t understand because as hard as I tried I couldn’t connect the idea of sacrifice with becoming more emotional. How could giving up something, even if it is illusory, make me more emotional? I was convinced that there was a key hidden in Gurdjieff’s words and that if I could decipher it, it would make my inner work easier and give me a shortcut to creating a permanent connection to higher centers.

It took me a while, but I did finally come to an understanding of what Gurdjieff was talking about. It didn’t turn out to be a shortcut, but it did give me a greater understanding of the way that I had buffered the idea of making my efforts to remember myself more consistent. The problem was that I was trying to think about the idea separately, rather than connecting it to my inner work. When we think about becoming more emotional, we usually believe that events are what make us emotional. But being more emotional can also be looked at as something that is not outside of our efforts to be present; it can be looked at as something that is contained within those efforts.

If I say to myself that I am going to give up my supper tomorrow, it’s unlikely that I will feel anything more than vanity or anxiety. But if I sacrifice the ‘I’s’ that want to think about tomorrow’s supper or the fear of unpleasantness connected with making efforts in the instinctive function, it becomes possible to give these up in order to be present. This changes the picture; suddenly I am—as Gurdjieff suggests—giving up illusions.

What this means is that if we want to create an emotional state, the things we need to sacrifice must be in the present moment. In particular we must sacrifice mechanicality. The idea is simple: there are many small, unnecessary illusions that we carry around with us that are supported by our mechanicality. If you are in the habit of watching TV while you eat, you can sacrifice watching TV and instead concentrate on being present to your meal. In a situation like this, what are you really giving up? In most cases what you are giving up is the illusion that you can watch television, eat, and remember yourself at the same time.

Maybe when you first awaken in the morning, you like to try to imagine how your day will go. If that is the case, then you can sacrifice your morning reverie and instead start your day by being present. The illusion you are giving up here is that you can do, that you are clever enough to predict the details of your day. Or maybe you walk or jog and allow yourself to imagine pleasant scenarios. Maybe you do this because you find jogging or walking boring. If that is the case, then you can sacrifice your pleasant dreams, and instead, try to divide your attention between your body and what you see in front of you. In this case what you sacrifice is the illusion that it is events, not your lack of effort, that make your outings boring.

In sense all we’re doing here is creating a space in our lives for self-remembering. Our lives can be made more deliberate in a way that incorporates inner work into our daily activities, but we have to want to do it.

So how does this lead to becoming more emotional? Basically sacrifice is a method of transformation, or to put it another way, a technique for diverting energy, usually lost in mechanicality, to internal aims. This process really only becomes possible with any consistency when the higher emotional center works because it is only in higher states that we have the scale and relativity to see our daily life as material for our work on self-remembering. In other words we must, to some extent, realize that the life around us is unreal before we are willing to give up our illusions.

What does it mean that the world we see is unreal? To me it means that life is passing, that it lacks a feeling of being substantial—or of having a positive existence—when compared to the time-expansive perception of higher centers. Most of our problems are only seen as problems because we have not observed them from the scale of the entirety of our lives.

For in and out, above, about, below,

‘Tis nothing but a Magic Shadow-show,

Play’d in a Box whose Candle is the Sun,

Round which we Phantom Figures come and go.

~ Omar Khayyam / Translated by Edward FitzGerald

The unreality of the second state seen from the third state may be compared to the memory of a dream. The dream feels unreal when we are in the second state in the same way the world feels unreal from the point of view of the third state. Really only the first conscious shock—self-remembering, being present, divided attention—has the power to bring us to the unreality of life. But we need to work on other lines as well. Change of attitude, right thinking, and work on stopping identification and imagination all lay the groundwork for the possibility of sacrificing our mechanicality. But before we can give up mechanicality, we first have to observe it and try to stop it; and before we can exchange it for something higher, we have to be able to see our lives and, to some extent, the world from the point of view of our work on conscious evolution. We need to begin to see our lives as material for inner work. Eventually, when the higher emotional center works, these lines of effort join, but at first they must be worked on separately. It is this inability to combine different lines of effort that gives a man number four the feeling that he is working in the dark.

There is much we can sacrifice. We can give up the idea of health.

I once said that they must sacrifice ‘faith,’ ‘tranquility,’ ‘health.’ They understand this literally. But then the point is that they have not got either faith, or tranquility, or health. All these words must be taken in quotation marks. ~ G. I. Gurdjieff

What does it mean to sacrifice health? To me it means giving up fear and worry about the instinctive center. We don’t stop taking care of our needs, but we do need to admit to ourselves that ill health is a part of the human condition. From the point of view of higher centers, the body’s life is so short that to identify with it and give it all our energy is short-sighted. So when we observe fear and worry about our health, instead of reassuring ourselves, which is usually imagination, we sacrifice our fears for self-remembering and being present. We give up the illusion of health and concentrate our efforts on connecting to higher centers, which have the possibility to observe the body as a temporary housing for the self.

The idea of sacrifice can have far-reaching effects on our work, but first we must be willing to take the next step: to begin to think in terms of consistent effort. We want to believe that a higher level means less effort. We want to be rewarded with rest. But in my experience a new level means that exercises and efforts that were impossible before become possible. Epictetus says, ‘If you would improve, be content to be thought foolish and stupid with regard to externals.’ In our terms this might read: if you want to be present, you must be willing to sacrifice, at least, the things that are incompatible with self-remembering. Why are we unwilling to make these sacrifices? Because we are still endeavoring to keep our illusions and because all our energy is diverted into preserving an imaginary world. But life is too short to have everything. We must learn to choose; we must think in terms of what are we willing to give up to connect to higher centers.

The idea of sacrifice can have far-reaching effects on our work, but first we must be willing to take the next step: to begin to think in terms of consistent effort. We want to believe that a higher level means less effort. We want to be rewarded with rest. But in my experience a new level means that exercises and efforts that were impossible before become possible. Epictetus says, ‘If you would improve, be content to be thought foolish and stupid with regard to externals.’ In our terms this might read: if you want to be present, you must be willing to sacrifice, at least, the things that are incompatible with self-remembering. Why are we unwilling to make these sacrifices? Because we are still endeavoring to keep our illusions and because all our energy is diverted into preserving an imaginary world. But life is too short to have everything. We must learn to choose; we must think in terms of what are we willing to give up to connect to higher centers.

Thank you for this article. Very helpful

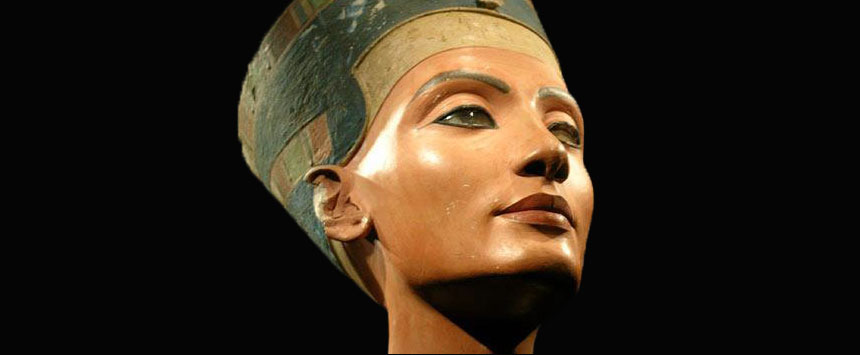

Why the bust of Nerfertiti? is the character somehow realted to the idea of sacrifice in the 4th way? or did you just put it as random egypcian element to symbolize the supposed egypcian-esoteric christianity-4th way connection roots?

Anyways, I appreciated the article and your thoughts. Thanks!

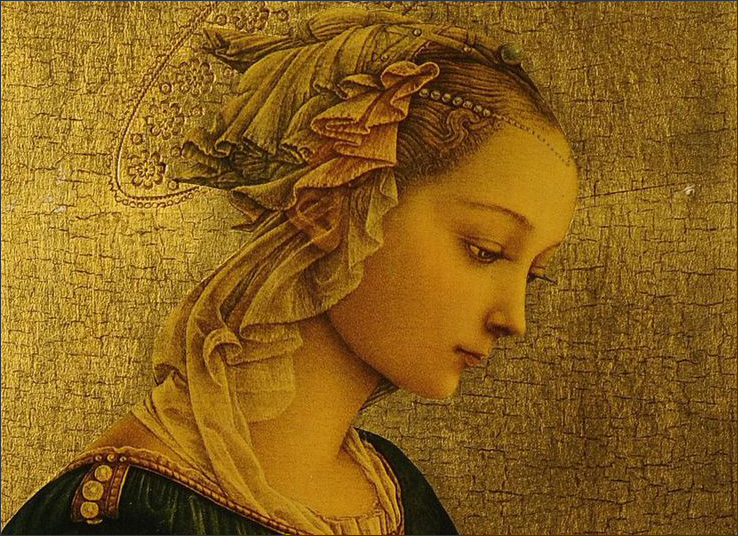

Hfosh: Sometimes a choice of an image is more emotional or perceptional than thematic. I’m always interested in finding art that I feel conveys higher worlds, especially world twelve and higher. It helps that I have traveled a great deal and seen many, many great pieces. I guess I hope that certain images will communicate–as much as is possible on a device–something of the power of the original piece and inspire people to practice the ideas I examine, which are all about connecting to those higher worlds.

Nice, thanks for the explanation. I’m courious now, if you have in mind a particular piece, or work of art, or group of pieces among all of what you have contemplated, which you would consider with the most power of evoking or transporting oneself into “higher worlds”, despite the subjective particularities or art affinities of each one.

Hfosh: Certainly Rembrandt and Leonardo and the best of of ancient Greek and Egyptian sculpture. Of course there many others. The impressionists are very good at conveying essence and can be quite refreshing. I talk about this in an article called When We Talk About Freedom. You might to look at it. All art has the potential to communicate higher worlds. Poetry for example. Rilke spent quite a bit of time trying to get into the right state in order to write his greatest poems. He talks about it in his letters.