First we have to admit that traveling doesn’t necessarily make us wise, because if that were the case, then I, and many of my friends, would be wiser than Goethe, than Montaigne, and than Shakespeare—all who traveled very little by modern standards.

No, I think we have to eliminate wisdom as a motivation and find other justifications for plucking ourselves up from our established lives and spending a lot of money to see ancient monuments, foreign customs, and strange climates.

What childishness is it that while there’s a breath of life

in our bodies, we are determined to rush

to see the sun the other way round?

~ Elizabeth Bishop

I have spent ten years of my life abroad, and I have to admit that in many cases my motivations for getting away were simple restlessness or dissatisfaction with where I happen to be. The same motivations seems to have driven the thirty-seven year old Goethe, well established in Weimar, to assume the name Moller and board a coach bound for Italy at three in the morning with no servant and little luggage. His letter to Karl August, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, his employer, makes it clear that he was feeling constrained by his duties in Germany.

I say nothing of how favorable these circumstances are at present and simply ask you for an indefinite leave of absence. The baths these two years have done a great deal for my health, and now I hope for an equal improvement in the elasticity of my mind. ~ Goethe

His travel diary, Italian Journey, would become one of the most famous travel books ever written. His journey lasted nearly two years, and though he talked about it, he never returned to Italy.

So does Goethe gives another justification for traveling? I mean to improve the elasticity of our minds. But can we really equate our experience of travel with Goethe’s? Are we saying that our minds have the same sophistication and receptivity as Goethe’s mind? The airlines and the travel agencies would have us believe that sophistication is the hallmark of the modern traveler, but the reality is something quite different. The primary justification of the modern tourist to see the world seems to be shopping and the snapping of photographs. They dip into another culture with their left toe and take away from it, not mental elasticity or greater understanding, but keepsakes and pictures. The keepsakes decorate their homes and their photographs are used to demonstrate the superiority of their experiences over the experiences of their friends. And really nobody loves a travelogue.

So does Goethe gives another justification for traveling? I mean to improve the elasticity of our minds. But can we really equate our experience of travel with Goethe’s? Are we saying that our minds have the same sophistication and receptivity as Goethe’s mind? The airlines and the travel agencies would have us believe that sophistication is the hallmark of the modern traveler, but the reality is something quite different. The primary justification of the modern tourist to see the world seems to be shopping and the snapping of photographs. They dip into another culture with their left toe and take away from it, not mental elasticity or greater understanding, but keepsakes and pictures. The keepsakes decorate their homes and their photographs are used to demonstrate the superiority of their experiences over the experiences of their friends. And really nobody loves a travelogue.

The traveler sees what he sees, the tourist sees what he has come to see. ~ G. K. Chesterton

Tourism is a deadly sin. ~ Bruce Chatwin

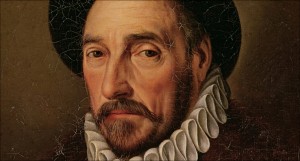

In 1580 Michel de Montaigne traveling at a pace of about twenty miles a day, journeyed from Beaumont to Rome—by way of Switzerland, Germany, and Austria—and in then back again. His trip took seventeen months. Traveling at the relatively old age of forty seven, Montaigne packed his carriage with books and medicine and visited spas as well as interesting towns and cities. He describes not only the sights and customs, but also records his instinctive battles—colic in Sterzing, gravel and dizziness in Florence, a toothache at La Villa. He also wrote about the difficulties in finding good horses and drivers. I wonder how many of us would have the courage to journey as he journeyed.

Byron kept no record of his travels, but his letters, because he traveled so widely, read like a travel book. His collected letters (nine volumes) are one of the most entertaining books I’ve ever dipped into.

For centuries kings and Emperors used exile as a punishment second only in terribleness to death. The poet Ovid was exiled from Rome to Tomis, a backwater on the edge of the Empire, for displeasing the Emperor Augustus. In exile, Ovid wrote Tristia. The first part details his sadness and desolation, and the second part takes the form of a plea to Augustus to end his unhappy exile.

Our native soil draws all of us, by I know not what sweetness, and never allows us to forget. ~ Ovid

Two thousand years later the Russian poet, Osip Mandelstam, wrote a collection of poems also called Tristia, which means ‘sad things’ or ‘sorrows.’ At the time, in 1922, he was a free man, but twelve years later he was arrested and threatened with exile in Cherdyn in the Northern Ural. After he attempted suicide, the sentence was lessened to banishment from the largest cities. For his new place of residence he chose Voronezh, where he wrote poems mourning his loss of simple pleasures.

Oh if only I could hoist a lantern on a long pole,

and, led by a dog, under the salt of stars,

with a rooster in a pot, arrive at the fortune-teller’s yard.

But the white of the snow stings my eyes till they hurt.

~ Mandelstam

These days, with the price of gasoline and the worldwide oil reserves drying up, we may again find ourselves in a period in history where the trouble and expense of travel hinders many of us from going far from home. It’s said that before the stream engine, most Americans lived out their lives within a fifteen mile radius of where they were born. Today fifteen miles is not even considered a long commute. But unless we come up with alternative energy sources and environmentally friendly cars and trains and planes, it seems likely that our days of widespread and far reaching travel are past their peak.

Globalization has also changed and will continue to change the way we think about travel. In my mind globalization makes travel less attractive because much of what is local is being replaced by something standardized. Hotels and food are probably the best examples of this. I was once taken to a McDonalds in the middle of Moscow by Russian friends, and not long before that I stayed in a Best Western hotel with a French woman in the town of Chartres, near the great cathedral. The more everything is everywhere the same, the more the allure of going someplace will be diminished. We generally seek difference, or local color, when we feel the need to escape our daily lives.

Another attraction to travel for me is being thrown together with people from different cultures. Once on a train from Saint Petersburg to Vilnius I stayed up all night talking to a Finnish man about occult ideas. On another train, this time from Moscow to Vilnius, I shared a compartment with three Russian soldiers who were on their way to hunt in Lithuania. When they found that I had lived in California, all they wanted to know was if I had ever seen a bear. In fact, I had once seen a bear tipping over the garbage can of my neighbor. That was enough to win them over. The four of us spent the rest of the night drinking their vodka, talking politics, and playing a Russian card game, called Fool, which I never mastered. On the same train a couple months later, I shared a compartment with a beautiful deaf woman. I spoke to her brother, who was seeing her off, and was so enamored with the two of them that I wrote a short story about their relationship, or what I imagined their relationship to be like.

Telling stories is the only conceivable occupation for a superfluous person such as myself. ~ Bruce Chatwin

Today people from different cultures can meet and speak on the internet. Though I love to hear people tell their stories, I haven’t yet been inspired to write about someone I talked to on facebook or twitter. I’ve thought about this, and I think that part of what is lacking is setting. Setting provides so much of the mood and context of a person’s story. To sit in the apartment of a Russian in Moscow tells me so much more than to know whether that same person reads Pasternak or listens to American jazz. Maybe I’ll find this kind of inspiration yet. Still, place is part of our stories. And the internet, for better and worse, effectively eliminates place.

Also we tend to flit about on the internet, jumping from one person to another. Travel forces us to spend an allotted amount of time with people we don’t know. On a flight from London to San Francisco I chatted about nothing with a priest who drank six or seven Bloody Mary’s. What was his story? On a flight from Athens to Rome I sat next to a Greek woman dressed all in black who laughed for no reason when we took off. What was her story?

I’m never quite at ease on a plane. There something disconcerting to my body about being so far above the earth. Like Montaigne I am not comfortable being jostled about.

By that slight jolt given by the oars, I somehow feel my head and stomach troubled, as I cannot bear a shaky seat under me. ~ Montaigne

Trains are my favorite means of travel. The people I’ve met on trains: the blind man who was dumped in my compartment by his companion in Copenhagen, or the young Italian girl who cried in her sleep on the night train from Paris to Venice, or the young man from Munich who, on a French train, wanted to tell me what he hated about Americans, or the brother of a English friend who told me the history of the Basque separatists on a dusty train bound for Madrid.

Of course there is always some risk of harassment; I guess that’s part of the fun. Once on cold winter morning on the border between Italy and Switzerland, my friend and I were kept from boarding our train by Italian soldiers just because we were Americans. They let us go as soon as the train pulled away and thought the whole thing was a great joke. We spend four hours in the freezing station waiting for the next northbound train. Another time an English customs official in Dover accused me of transporting illegal drugs when he found a bag of loose chamomile tea and a bottle of homeopathic pills in my luggage. After he had the questionable substances tested, he was so apologetic that he helped me carry my bags to my train, which I boarded just as it was starting to move. And on a night train from Warsaw to Cracow, my friends and I had the bad luck of traveling with a local football team and half their fans. They screamed, and drank, and vomited all night.

But as Shakespeare’s clown in As You Like It says: Travelers must be content.

But as Shakespeare’s clown in As You Like It says: Travelers must be content.

For Americans the most popular kind of travel is the road trip. The automobile certainly has its advantages. In my youth my friends and I thought nothing of driving a thousand miles to New Orleans or Florida. During my time in Europe I once drove with a woman from Venice into the Swiss Alps, where we spent some time in a town where she had made a film and then went to visit Rilke’s grave. The grave with its wonderful inscription, ‘Oh Rose, pure contradiction, to be nobody’s sleep under so many lids,’ is set against the outside wall of a medieval church, which is perched on top of a miniature mountain. To get there the traveler has to climb a rock stairway carved into the side of the mountain. The view from the top overlooks the alpine valleys and peaks. To travel there and recite his poems at his grave has become a modern pilgrimage.

At least once in his lifetime, a Muslim is expected to undertake a pilgrimage to Mecca. In America and Europe the pilgrimage had lost some of its favor. Most travelers who visit the great churches and cathedrals of Europe do so because of their great beauty or their architectural interest, not because of their religious significance. To be pious in our times is not popular. But then Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales may be our greatest pilgrimage book, and it is anything but pious.

When someone said to Socrates that a certain man was not improved by his travels, he replied, ‘I am not surprised, he took himself along as a companion.’

What exile leaves himself behind? ~ Horace

Traveling may not make us wise, but if we go about our travels with open eyes and an open mind, it should at least give us scope, and perhaps, with a little effort on our part, a greater tolerance for the ways of others. I find it hard to talk to a man who knows little of history and little of what the rest of the world thinks. This kind of man is too often trapped by his own opinions.

That said, many great men have traveled little. The mind and soul can remain unfettered, even when the legs are bound. And sometimes we have to choose. If it is a question of having no money to travel and the time and energy to give to projects that interest me, or, on the hand, to give my interests (and my mind) to other men’s priorities so that my legs can be free for three weeks every year, I will always choose the latter.

It’s a kindness that the mind can go where it wishes. ~ Ovid

Of course modern life is complicated. Our life choices are not often our own but are constrained by lack of money or by ill health.

And there is a kind of sadness to traveling. Travelers easily become wanderers and lose all sense of home.

People who spend their whole lives travelling abroad end up having plenty of places where they can find hospitality but no real friendships. ~ Seneca

This is from Shakespeare, who it is said never left England:

A traveler! By my faith, you have great reason to be sad. I fear you have sold your own lands to see other men’s; then to have seen much and to have nothing is to have rich eyes and poor hands.