Travelogue 1

The idea of home always perplexed me.

Is it necessarily the place we were born?

Or can it be the streets of a city we loved,

where the soles of our shoes were most worn?

I should have missed Paris with its crowded museums,

late-night cafes, its improbable chapel domes,

and the Seine snaking through its center,

but I never thought to call it home.

Once, in winter, while in Saint Petersburg,

I took a bus to the shore of the North Sea,

and stood in bitter winds and saw sand under snow,

and frozen waves as far as the eye could see.

I thought it a monstrous, uninviting sight,

but the locals seemed quite at home, they pulled sleds,

and sat at frigid picnics around fires on the beach,

happy to drink vodka and eat sweetbreads.

And then there is California, with its invented name,

its rattlesnakes under the porch, its deserts,

its parks with giant sequoias, ribbon-like waterfalls,

and sunsets that are so lovely it hurts.

There, only two seasons are defined: the rainy one,

and the summer with its perfectly blue days;

a formal winter is missed, but a short drive takes you

to mountains where sometimes there is snow in May.

A place of liberal cities, valley towns, and suburbs

of grazing deer. The travelers want to know about bears.

Yes, I have seen a few. But home? No. Here is a place

where two-thirds of its people were born elsewhere.

I wonder if it’s right that we find it so easy

to exchange winter fields for gardens in the sun.

Will one more stamp in our passport finally

make us into the person we want to become?

Is it not childishness to expect to find happiness

in the east when we can’t find it in the west,

to find a home surrounded by strangers

who must cater to us because we are their guest?

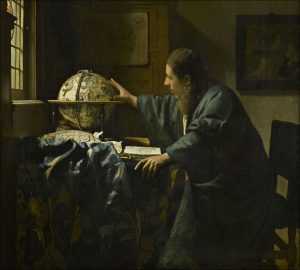

Montaigne, after ten years of self-imposed exile

left the tower that had been his solitary home,

and, at the torturous rate of twenty miles

a day, journeyed from Beaumont to Rome.

He packed his carriage with books and medicine,

visited spas, and kept a record of when he was sick

and where: gravel and dizziness in Florence,

a toothache at La Villa, in Sterzing, colic.

Shakespeare, they say, never left England.

But his plays are populated with strange islands,

shipwrecks, Italian merchants, daughters abandoned,

Danish ghosts, and wives torn from their husbands.

His travelers have a good reason to be sad:

to see other men’s lands they have sold their own.

They lie in the forest with rich eyes and poor hands

and speak of the virtues of being alone.

You say that I am not that old, I am not dead yet,

there is still time for one more hurried goodbye,

one more drive along the coast, one more sunset

like a fantastic angel spread across the sky.

In truth, I would have missed the rush to the station,

and the fraternity of the long drive,

I should have missed the people who were happy

to let me become a part of their lives.

Still, is greatness no more than greatness seen?

What is this restlessness that keeps us on the move?

Where is the settled spirit we wanted to become?

And what is it that we are trying to prove?

When you are dead—a ghost haunting your funeral—

what will you think when you hear people say:

Oh, she went to this place and then to that place,

she saw so much greatness in her day.

****